Amitabh Bachchan probably doesn’t know it, but he is big in Somalia. So big that he even has his own Somali nickname. SAMIRA SAWLANI reports from Mogadishu on how Bollywood became an integral part of Somali culture – and how, over the decades, and through everything that Somalia has been through, it has remained so.

“You know Amitabh Bachchan? Shah Rukh Khan? I Am a Disco Dancer?”

On arrival in Mogadishu, I was not expecting to be greeted with Bollywood references wherever I went. But it turns out that Somalia is enchanted by the drama and the romance of Indian cinema — and has been for decades.

Although Turkish TV shows may be garnering much more influence now, Indian films remain a firm favourite with Somalia’s population.

“Indian films arrived in the country soon after Somali independence in 1960 and took the country by storm,” says Bashir Looyan, a banking executive and a self-confessed Bollywood film buff. “At one point Mogadishu had approximately 10 cinemas (this then rose to 18), many of which would screen Bollywood films. We did not have subtitles or dubbing in the 1970s and early 1980s, yet somehow everyone understood what was going on.”

Newspaper listing showing Bollywood films on show in Mogadishu.

The screening of a new film would often be a major event. A vehicle would drive around neighbourhoods announcing the names of new releases and who was starring in them. As excitement built, groups of young people and families made plans to convene at the cinema that same day. Prior to the civil war, which left Somalia’s city fundamentally altered, Mogadishu was known for its stunning open-air cinemas.

“These were a charming part of life in the city,” says communications consultant Fatuma Abdulahi, who has vivid memories of her childhood years watching Bollywood films “under the stars with a nice breeze”.

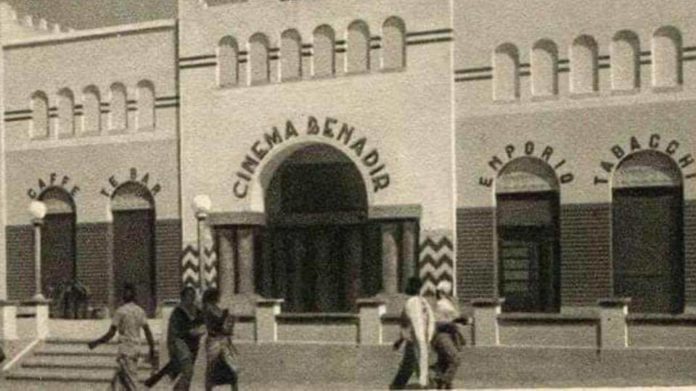

Cinema Super, Cinema Afrika, Cinema Somaliya, Cinema Nasar, Cinema Hadramout: these were just some of the places dotted around the city where crowds would gather in anticipation of the latest blockbuster. Although Italian and Hollywood films were also screened, it was Bollywood that really brought the crowds out.

Tickets cost as little as one Somali shilling, and screenings would take place from late afternoon to night time. Many moviegoers would finish up their days by relaxing in one of Mogadishu’s many restaurants or cafés before heading to the cinema for the 8pm show.

Khadra Mohammed told of how she would sneak out for one of the earlier shows with her sisters and friends, and then rush back home in time to prepare dinner. “I think in many ways so many of us dreamt of having that perfect Bollywood film love story; that is what those films gave us, a fantasy. And Mogadishu’s open-air cinemas provided the perfect atmosphere to enjoy this and fall into a daydream.”

Amitabh Bachchan is still Somalia’s favourite Indian actor, while the most popular film from that era is 1982’s Disco Dancer

Whichever category you fell into, one thing was certain: Somalia had Bollywood fever. It went beyond just a hobby or something to do on weekends. The films would be the topic of debate and discussion, with some of the more popular Bollywood actors even given Somali nicknames.

For example, global superstar Bachchan is still known as Cali Dheere, which translates to Tall Ali, and Amrish Puri, famous for playing some of Bollywood’s best-known villains, was referred to as Indha Guluus, which means Button Eyes.

Bachchan is still Somalia’s favourite Indian actor, while the most popular film from that era is 1982’s Disco Dancer. The rags-to-riches story starring Mithun Chakraborty was such a hit that even now any mention of the film has people humming the catchy title song.

“We all wanted to dance like Mithun. We were rooting for him against the bad guy. That film captured our imagination,” says businessperson Abdiaziz Nur.

Among the romantics, though, Bachchan’s 1976 Kabhi Kabhie remains the ultimate Bollywood film.

“Kabhi Kabhie was my absolute favourite,” says Looyan.

The film’s title song in particular took Mogadishu by storm. Its poetic lyrics, against the backdrop of a harmonious melody, was a huge hit. Forty-three years on, it is one that Somalis of that generation remember fondly.

“It was the romance and the mushy lyrics which won hearts in Somalia,” says Abdulahi.

Bollywood’s influence went beyond entertainment, also swaying fashion and style. Some Somali brides would choose wedding outfits that had an Indian flair. This was a trend also spotted among wedding guests, according to Mohammed. “Me and my sisters would go to the tailor and describe some of the outfits we had seen in an Indian film and ask them to make it that way.

“The most important part was seeing the clothes and the hair and the make-up,” says Mohammed. “Many of us girls would try to style our hair like Rekha and Hema Malini.’’

Hema Malini was the ultimate Bollywood “dream girl”.

Talk about Bollywood to Somalis for any length of time and Malini’s name is sure to come up. Bollywood’s “dream girl” stole hearts in Somalia to the extent that young men would refer to women they had a crush on as Hema Malini.

This trend for Bollywood-based nicknames did not end there, says filmmaker Abdisalam Aato.

“If you were a good dancer, you would be called Mithun, the lead actor in Disco Dancer; display villainous traits and you became Gabar after the famous villain in Sholay.”

But Bollywood was inaccessible to those who could not visit cinemas because of financial constraints or where they were located. This changed in the late 1970s when VCRs arrived in the country.

“Once a family got a TV and VCR, everyone in the neighbourhood would gather at their home to watch Indian films. Words like bachao [save me], which were common in films at the time, became part of our vocabulary,” says Aato.

All this would come to a halt in 1991, when the Siad Barre regime was overthrown and civil war ensued. The incoming Islamic Courts Union, a rival administration to the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia, went on to ban cinemas, films and even the dubbing of films into Somali, Aato explains.

Hindi words like bachao became part of our vocabulary

Many Somalis left the country, seeking safety in Kenya, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada, taking their love of Bollywood with them. Ironically, Indian films were one method the Somali diaspora would use to reinforce their sense of home. Zuhaira Ali was just a few months old when her parents left Mogadishu for Nairobi, setting up home in Eastleigh, referred to as Nairobi’s Somali hub.

“For the first years of my life my dad called me Kajol after his favourite Bollywood actress. He would get all the latest Indian films on DVD and so our house was often filled with neighbours, friends and family. The minute films starring Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan or Akshay Kumar arrived, everyone would come together. Those were the stars everyone wanted to watch,” she says.

An abandoned cinema in Mogadishu.

Now, as Somalia recovers from conflict, the demand for Bollywood films is on the rise again, says Nur Abukar of Fanproj Productions Studio in Mogadishu, which does voiceovers, dubbing and translation. This has provided jobs for those who speak Hindi and Somali.

“Many of them learnt Hindi while studying abroad in India, but there are also those who learnt simply from years of watching Indian films and reading the subtitles. Each person is given the role of a specific actor. So, for example, one person is responsible for doing the voice of Shah Rukh Khan in all his films.”

Fanproj has grown over the past four years. “Turkish and Indian dramas are popular, but Indian films still dominate the market,” says Abukar.

WATCH: Cali Dheere stars in Bade Miyan, Chote Miyan

Photos: provided by author