The Red Sea has been the focus of accelerating competition in recent years, with many Gulf and Middle Eastern countries expressing their interest in the region

The Red Sea region has been the focus of a struggle for power and influence in recent years, especially since the outbreak of the civil war in Yemen in March 2015. The whole of the East African coast from Sudan to Somalia is now in the sights of competing Arab Gulf and Middle Eastern countries.

The competition was accentuated with the intensification of the crisis in the Gulf in 2017, with Qatar on the one side and Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt on the other. The present rivalry over the African coastline of the Red Sea has produced geopolitical realignments that will have lasting consequences.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia are at the forefront of the Arab-international coalition against the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Jeddah, the Saudi Arabian port city on the Red Sea, also hosted the signing of a historic peace agreement between old foes Ethiopia and Eritrea in the presence of Saudi King Salman in September this year.

These two countries in the Horn of Africa have been in a “cold war” for the past 20 years because of a border dispute that degenerated into military conflict between 1998 and 2000. A first agreement to settle the dispute, signed in Algiers in June 2000, was a dead letter, but in a surprise announcement new Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed indicated in June his willingness to apply it. Events then moved towards the signing of September’s Jeddah Accord.

The UAE played a leading role in coordination with the Saudis in pushing Addis Ababa to settle its border dispute with Asmara. As a sign of recognition, Ethiopian and Eritrean leaders Ahmed and president Isaias Afwerki accepted Saudi Arabia as a mediator in sealing their reconciliation.

The civil war in Yemen largely explains the interest of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in this strategic area of the southern Red Sea, which is crucial for the success of military operations against the Houthis and the effectiveness of the blockade imposed by the international coalition on the Yemeni coastline to prevent the smuggling of weapons from Iran.

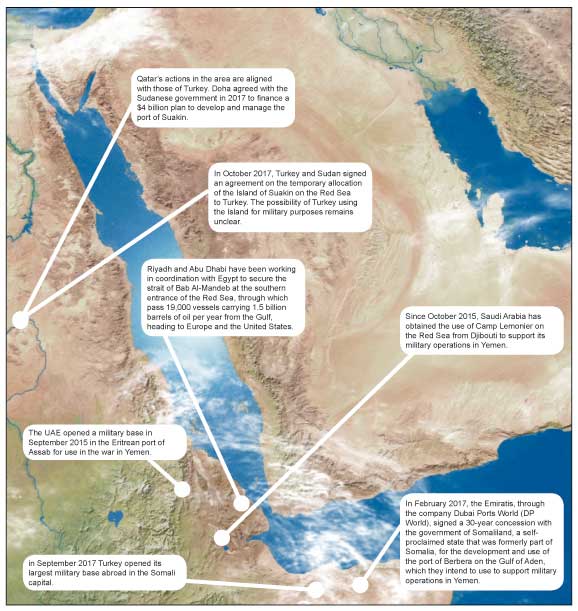

Since October 2015, Saudi Arabia has obtained the use of Camp Lemonier on the Red Sea from Djibouti to support its military operations in Yemen. It announced in December 2016 that it would turn the Camp into a large military base.

For its part, the UAE opened a military base in September 2015 in the Eritrean port of Assab for use in the war in Yemen. In February 2017, the Emiratis, through the company Dubai Ports World (DP World), also signed a 30-year concession with the government of Somaliland, a self-proclaimed state that was formerly part of Somalia, for the development and use of the port of Berbera on the Gulf of Aden, which they intend to use to support military operations in Yemen.

The Emiratis pledged $440 million to develop the port located in the western part of Somaliland. Another Dubai government-owned firm, P&O Ports, signed a 30-year deal in April last year for the development and use of the port of Bosaso on the eastern side of the Gulf of Aden with the government of the semi-autonomous Somali region of Puntland. The contract provides for $336 million in investment to expand and modernise the port.

Securing their oil exports to Europe and the United States is another reason for the rush of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to set up outposts in the Red Sea, particularly in a context marked by the American lack of interest in the Middle East since the days of former president Barack Obama.

To do so, the two countries have been working in coordination with Egypt to secure the strait of Bab Al-Mandeb at the southern entrance of the Red Sea, through which pass 19,000 vessels carrying 1.5 billion barrels of oil per year from the Gulf, according to the Centre for International Maritime Security, an international think tank.

The strait is in a dangerous region that has been witnessing two civil wars, in Yemen in the east and Somalia in the west. While the risk of piracy off the coast of Somalia has been reduced, the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen threatened in January to block the strait if the Saudi-led coalition continued its advance towards the strategic Yemeni port of Hodeida on the Red Sea.

TENSIONS AT SEA

The renewed tensions between the United States and Iran and the re-imposition of US sanctions against Tehran have pushed the latter to threaten to stop oil traffic in the Gulf by blocking the Strait of Hormuz.

This threat has prompted Saudi Arabia to look for an alternative to the shipping route, which it has found in a pipeline that would route its oil exports across the Red Sea. Riyadh believes that its security is dependent on that of the Red Sea and the containment of the Iranian presence on its coasts, and for this reason it has developed its naval fleet in the Red Sea. It has also urged Sudan, Djibouti and Somalia to cut ties with Iran, and in September 2014 Khartoum closed Iranian cultural centres in Sudan and expelled diplomats from the Islamic Republic from the country.

In January 2016, Sudan expelled the Iranian ambassador in Khartoum, and Djibouti and Somalia broke off diplomatic relations with Iran following an attack on the Saudi embassy in Tehran after the execution of a Shia cleric in Saudi Arabia. On the day of Mogadishu’s announcement of the breaking-off of relations with Tehran, Riyadh pledged $50 million in aid to Somalia.

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are also seeking to isolate Qatar, with which they have been in conflict since June 2017. They have succeeded in this regard with Eritrea, which was close to Tehran and Doha until 2015. Asmara had previously received assistance from Iran and granted facilities to the Iranian navy in the port of Assab.

Doha had been deploying its good offices in the border dispute between Eritrea and Djibouti in the region of Cape Doumeira (Ras Doumeira) on the Red Sea. It had been maintaining a peacekeeping force of 450 soldiers in this border region to help reach a peaceful settlement to the conflict, but with the outbreak of the war in Yemen and the UAE’s involvement in it, Asmara changed its stance in favour of the Saudi-led coalition. It broke off its relationship with Tehran and authorised Abu Dhabi to use the port of Assab. It also expelled the long-standing Houthi mission in Asmara and sent 400 soldiers to participate in the war in Yemen alongside Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Eritrea is also supporting the Saudis and Emiratis in their conflict with Qatar, and in return it has received oil assistance and the modernisation of its electricity grid from Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

Economic interests also explain the action of Saudi Arabia and the UAE towards Ethiopia. In a visit to Addis Ababa last June, UAE Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Zayed Al-Nahyan pledged $1 billion to the Ethiopian central bank to support the country’s foreign currency reserves and promised another $2 billion investment in tourism, renewable energy and agriculture.

Abu Dhabi is also planning to build an oil pipeline linking Eritrea to Ethiopia and Assab to Addis Ababa. Landlocked Ethiopia started extracting oil on a pilot basis from reserves in the southeast of the country in June, and it will need access through Eritrea to export it. The announcement of the agreement came after a meeting in Addis Ababa in August between the Ethiopian prime minister and Emirati Minister of International Cooperation Reem Al-Hashimi.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia also intend to increase their investment in the Ethiopian agricultural sector, which employs 85 per cent of the workforce. Ethiopia, which has a surplus of water, has vast arable land, only a quarter of which is cultivated.

ETHIOPIAN INITIATIVES

Even though Saudi and Emirati aid encouraged the Ethiopian prime minister to reconcile his country with Eritrea, Ahmed has had other reasons besides the economic assistance his country badly needs to put an end to the state of war with his Eritrean neighbour.

Since he came to power in April, Ahmed has embarked on a broad campaign of internal reforms and external initiatives that has made making peace with Asmara indispensable. One of the most important of these initiatives at the external level has been his desire to resuscitate the maritime power of Ethiopia, with Ahmed declaring in June this year that “we should strengthen our naval capacity.”

Since the independence of Eritrea and its secession from Ethiopia in May 1993, the latter has become a landlocked country devoid of its former access to the Red Sea, and this has forced it to dismantle its naval fleet. The state of war with Eritrea prevailing since 1998 has made the situation more difficult, with the closure of Eritrean ports to Ethiopia and the latter’s obligation to use the more distant and therefore more expensive port of Djibouti for its foreign trade.

Addis Ababa depends on Djibouti for 70 per cent of its trade with the outside world. The rapid development of the Ethiopian economy, which has grown from $8 billion in terms of GDP in 2000 to $80 billion in 2017, has made it necessary to reduce the country’s reliance on the port of Djibouti and to find alternatives for its growing foreign trade.

The most practical and least expensive solution would be to reuse the ports of Eritrea. It was therefore not surprising that one of the first decisions taken after the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between Addis Ababa and Asmara was the reconstruction of the roads connecting Ethiopia to the two Red Sea ports of Eritrea, Massawa in the north and Assab in the south.

The reconstitution of the Ethiopian naval fleet also requires access to foreign ports on the Red Sea and agreements with countries on the East Coast of Africa. Ethiopia has stepped up initiatives in this regard in recent months, strengthening ties with its neighbours, especially Eritrea.

In July, it agreed with Asmara to jointly develop the Eritrean ports on the Red Sea. In May, it signed an agreement to take a stake in the main port of Djibouti. Two days later, it signed a similar agreement on the largest Sudanese port in the Red Sea, Port Sudan. In March, it acquired a 19 per cent stake in the port of Berbera in Somaliland.

TURKEY AND QATAR: The first Arab Gulf player on the west coast of the Red Sea in the 2000s, Qatar sought to position itself as the mediator of choice in the conflicts in the region, hosting peace talks on Darfur in Sudan since 2008 and then in the border dispute between Eritrea and Djibouti around the region of Cape Doumeira on the Red Sea.

It maintained a peacekeeping force in this border region to help find a peaceful settlement. But since the outbreak of the war in Yemen, Asmara changed its position in favour of the Saudi-led coalition, seeing it as an opportunity to break the country’s isolation imposed by Ethiopia.

In line with its changing position vis-à-vis the Yemen war, Eritrea chose to side with the Saudis and Emiratis in their conflict with Qatar, which then withdrew its peacekeeping contingent from Cape Doumeira in June 2017. Qatar’s influence in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East in general has weakened since the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt in 2013.

However, the competition for regional influence in the Horn of Africa between Qatar on the one side and Saudi Arabia and the Emirates on the other has extended to Somalia, close to the vital oil routes crossing the Gulf of Aden. The recent rapprochement between Somaliland and Puntland, on the one hand, and the UAE and Saudi Arabia on the other, has been opposed by Somalia’s parliament and president Mohamed Mohamed Abdullahi, who is close to Qatar and Turkey.

Somalia is an ally of Doha, and relations have strengthened since the break between the latter and Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, Manama and Cairo. The internal Somali divisions have been the result of the weakness of the central government, which is unable to control the entire country, and they have allowed the Gulf crisis around Qatar to determine and reinforce Somali fragmentation.

The central government’s support for Qatar can be explained by the fact that Doha financed the president’s election campaign in 2017 and pledged $385 million in aid to the Somali government in infrastructure, education and humanitarian assistance. In Somalia, Qatar’s action is aligned with that of Turkey, which has sided with Doha in its dispute with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt. The two countries’ alliance was sealed by Turkey’s opening of its first military base in the Middle East in Qatar in April 2016 in an indication of its support of Doha against the diplomatic isolation imposed by the other Gulf countries.

The two countries have been acting in tandem in the Horn of Africa, like in other regions. In Somalia, where almost all their investments are in Mogadishu, they focus on supporting the sitting president, and in September 2017 Turkey opened its largest military base abroad in the Somali capital, massively strengthening its presence in East Africa.

More than 10,000 Somali soldiers will be trained by Turkish officers at the base of Mogadishu, which, costing $50 million, reflects the growing ties between Mogadishu and Ankara, which also has its largest foreign embassy in Somalia.

Turkey’s relations with the Horn of Africa date back to the former Ottoman Empire, and the government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has become a close ally of the Somali government in recent years. Turkey has built schools, hospitals and infrastructure in the country and provided scholarships for Somalis to study in Turkey. The Turkish Al-Bayrak Group has been operating the port of Mogadishu since September 2014.

Erdogan has also visited Mogadishu twice, and when he made his first trip there in 2011 he became the first non-African leader to visit the war-torn country in 20 years. When the radical Islamist group Al-Shabab, backed by Al-Qaeda, withdrew from Mogadishu in 2011, Turkey launched famine-relief operations in the country, opening the door to projects that now make it the largest foreign investor in Somalia.

Trade between the two countries has grown rapidly. In 2010, Turkish exports to Somalia stood at $5.1 million. But by last year they had reached $123 million. In the space of six years, Turkey has moved from being Somalia’s 20th-largest source of imports to its fifth. One Turkish official said at the time that the Turkish military base in the capital was in line with Ankara’s priority of expanding arms sales “to new markets”.

Turkey has also moved closer to Sudan and Qatar. Following the lifting of US sanctions on Sudan in October 2017, Erdogan made the first visit of a Turkish president to Khartoum in December of the same year. His arrival was timely since Sudan was desperately looking to attract foreign investment after two decades of a trade embargo and other sanctions that had cut the country off from much of the global financial system.

During the visit, the two countries signed a series of agreements on Turkish investments for the construction of the new Khartoum airport and private-sector investment in cotton production, electricity generation and the construction of grain silos and mills. The economic relations between Turkey and Sudan are nevertheless older than the lifting of US sanctions. In 2014, Sudan leased to Turkey nearly 780,000 square kilometres of agricultural land for 99 years.

The most important agreement signed during Erdogan’s visit was on the temporarily allocation of the Island of Suakin on the Red Sea to Turkey. The latter will now be responsible for rebuilding it, including the construction of docks to maintain civilian and military vessels.

The possibility of Turkey using the Island for military purposes remains unclear. Under the former Ottoman Empire, it was an important point in the journey of Muslim pilgrims traveling from the African countries to Mecca and Medina to complete their pilgrimage, as well as for traders from East Asia to Africa and to Europe.

Like in Somalia, Qatar’s actions in the area are aligned with those of Turkey. In the wake of the rapprochement between Ankara and Khartoum, Doha agreed with the Sudanese government three months after Erdogan’s visit to finance a $4 billion plan to develop and manage the port of Suakin.

The project, planned to be completed in 2020, is conceived as a logical extension of Turkey’s development of a naval facility in Suakin.