After a bank pullout, Washington state’s Somali Americans struggle to send money to their families in Africa.

When a California bank quit handling wire transfers toSomalia earlier this month, Abdulhakim Hashi, owner of Hashi Money Wiring in SeaTac, suddenly had no place to deposit his customers’ cash and checks.

When a California bank quit handling wire transfers toSomalia earlier this month, Abdulhakim Hashi, owner of Hashi Money Wiring in SeaTac, suddenly had no place to deposit his customers’ cash and checks.

The long-feared pullout by Merchants Bank — which handled more than half of all remittances from the United States to the East African nation — shut down overnight a major legal channel for Somali immigrants to send money back home.

The long-feared pullout by Merchants Bank — which handled more than half of all remittances from the United States to the East African nation — shut down overnight a major legal channel for Somali immigrants to send money back home.

That money not only pays for food, medicine and other sustenance, but makes up a significant share of Somalia’s economy.

The worries are particularly widespread in Washington state, which is believed to have the nation’s largest population of Somali Americansoutside of Minnesota and Ohio.

In Washington, Merchants Bank had been the sole financial institution willing to assume the risks and hassles of handling transactions to Somalia, which lacks a functional commercial banking system and parts of which are controlled by al-Shabab, an Islamist group identified by the U.S. government as terrorists.

In Washington, Merchants Bank had been the sole financial institution willing to assume the risks and hassles of handling transactions to Somalia, which lacks a functional commercial banking system and parts of which are controlled by al-Shabab, an Islamist group identified by the U.S. government as terrorists.

“How will local Somalis send money in the future? I have no ready answer to this question,” said Hashi, one of a group of bonded and licensed Somali money-transfer operators clustered in Tukwila, SeaTac and elsewhere around South King County.

The financial disruption — and concerns that it might push Somali Americans to black-market channels — is pushing federal officials to weigh possible emergency solutions.

On Thursday, U.S. Rep. Adam Smith of Bellevue and three members of Congress from Minnesota will meet with representatives of the U.S. Treasury Department, National Security Council, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and six other agencies.

On Thursday, U.S. Rep. Adam Smith of Bellevue and three members of Congress from Minnesota will meet with representatives of the U.S. Treasury Department, National Security Council, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and six other agencies.

The lawmakers, including Rep. Keith Ellison and Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Al Franken, had pressed Secretary of State John Kerry for quick action on what they called both a humanitarian crisis and a national-security risk.

Seattle Mayor Ed Murray also wrote Kerry, saying Seattle’s Somali residents are “terrified that they can no longer support their families who rely on their help.”

Smith, a Democrat whose 9th Congressional District includes Tukwila, Renton and Federal Way, said federal regulations help ensure that money from abroad doesn’t get funneled to terrorist organizations. In 2014, a Kent woman was indicted on charges alleging that she ran a fundraising conspiracy to support al-Shabab.

Merchants Bank began notifying some money-transfer operators last May that it was terminating their accounts, citing “ever-changing regulatory requirements and expenses.”

The bank’s move, however, apparently was not triggered by any recent new regulations or specific concerns about illicit funds flowing to Somalia.

Smith said “this is just incredibly important” to find an immediate alternative way to route the money. One option, he said, would be for the Federal Reserve to step in for a commercial bank.

The Fed could collect the money from local transfer agents and forward it to an overseas bank, in Dubai or elsewhere, from which the money would get parceled out to a counterpart agent, then to paying agents for distribution in Somalia.

Somalia, which lacks an effective central government, is particularly dependent on remittances. Somali emigrants send an estimated $1.3 billion a year from around the globe, $215 million of that from the United States.

The absence of a commercial banking system drove the Somalis to establish an extensive “hawala” (“transfer” in Arabic) network that gave way to money-transfer operations, said Scott Paul, senior humanitarian policy adviser at Oxfam America. So Somali money-transfer operators also serve customers in Ethiopia, Kenya and the rest of Africa.

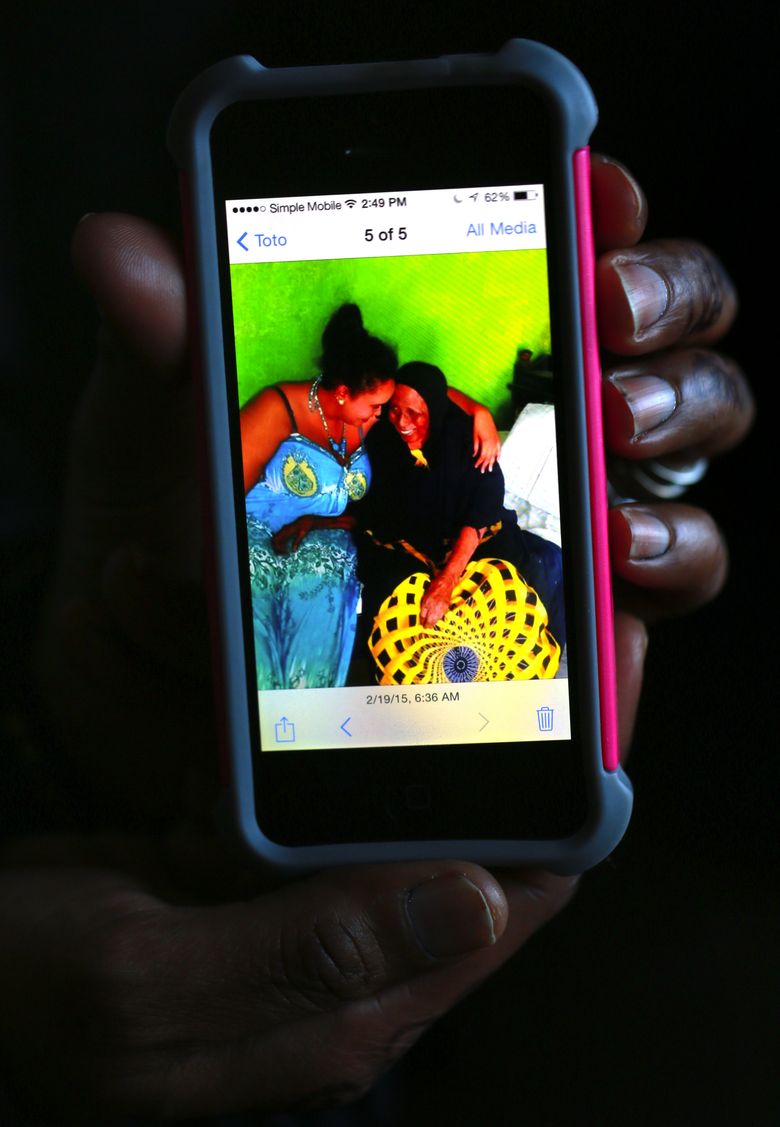

Omar Mumin, chief executive of Seattle-based charity group Global Aid Against Poverty, sends about $300 a month to his 70-year-old mother in Kenya, helping support his three divorced sisters and four of their children. Their village has no Western Union or MoneyGram. But it does have a Somali money-transfer office.

Mumin is worried Merchants Bank’s pullout could keep his mother from receiving money to pay her rent and buy medicines.

“Stopping the money transfer has resulted in panic throughout the community here in Seattle,” Mumin said.

A Somali friend of Mumin is despairing that he can’t send money to his nine children back home, money needed to keep them in school.

A Somali friend of Mumin is despairing that he can’t send money to his nine children back home, money needed to keep them in school.“Such problems will result in young men losing hope and trying to find hope elsewhere,” Mumin said. That “will be a lose-lose situation for both the international community and the Somali government.”