This is the Fifth of a reproduction of a series of historical notes, articles, tracts and academic discourses to recall landmarks in the history of Somaliland from 1884 which highlight events leading to the country’s two independences of 1960 & 1991.

The first British campaign in Somaliland ended in July 1901 with Mullah Sayyid Muhammad ‘Abdullah Hassan and his followers fleeing into sanctuary in Italian territory. The British force of local levies recruited by Lieutenant Colonel Eric J.E. Swayne, Indian Army, was paid off except for 600 men who were retained to become the nucleus of the 6th King’s African Rifles (6 KAR). Swayne was called to London for discussions and Captain M. McNeill DSO (Argyle & Sutherland Highlanders) took over the military command.

The reduction of the levies was organised by giving each soldier a gratuity of two captured camels besides his pay, whilst those men who signed on to stay in service for a further three years received a third camel. Any men who wished to take camels in lieu of pay were allowed to do so if they exchanged 25 rupees for each camel (this indulgence had to be withdrawn before all the companies were discharged because the stock of camels ran short). Fifteen camels were given to the nearest relatives of every man killed in action, and those who had been wounded received a compensation of up to seven camels, according to the nature of their wounds. Needless to say this distribution of camels, and the quality of the camels, became subjects of intense and lengthy debate between the Somali recipients and the adjudicators. Half of the men remaining in service went on leave for six weeks, followed by the remaining men after the first party had returned.

The plan for the formation of 6 KAR envisaged a battalion of 10 British officers, 8 Somali officers and 1,037 Somali other ranks, formed into three infantry companies and a camel company. The battalion would be supported by quickly-raised levy companies as and when required. 6 KAR nominally came into service on 1st January 1902, with 100 men stationed at Berbera and 600 located up-country (500 infantry and 100 mounted on camels), but it was not until campaigning ceased in 1904 that the regiment was officially designated and recognised by the Foreign Office. However contemporary accounts use the title 6 KAR during the years 1902 to 1904 to distinguish between the men on three-year engagements and the addditional levies raised for short periods. The British officers who had served in the first campaign were asked if they would like to serve for a further three years in the Protectorate, and several of them agreed to do so and were posted to 6 KAR.

Preliminary moves

Preliminary moves

McNeill oversaw the construction of a fortified base at Burao which was designed by Lieutenant A.C.H. Dixon (West India Regiment). Dixon used his experience of operations in West Africa to build a stockade, using vertical poles spaced one metre apart. The spaces between the poles were filled with dry-stone walling cemented by earth and brushwood, which formed a mortar when water was poured over. Sand bags topped the wall at a height of about a metre and a half, whilst two concentric thorn zarebas circled the stockade. The breadth of these zarebas was about four metres for the inner one and about six metres for the outer one. The zarebas had barbed wire entangled through them and they were both so low that they did not obstruct defending fire.

Traverses (protective projecting walls) were built against the inside of the stockade at intervals, and two Maxim gun positions were constructed on corners. The bush outside the outer zareba was cut down for a distance of around 730 metres, giving a good field of fire for the defenders. The rear or north side of the stockade was positioned on a sheer bank about ten metres high which overlooked the river and the Burao wells that were 150 metres away. The finished stockade could not be destroyed by fire, and enemy artillery would have been needed to reduce it.

Left: A Yao Askari of 2 KAR in Somaliland

Meanwhile the Mullah infiltrated his dervishes back into British territory and re-gained his ascendancy over the Dulbuhante tribal territory, as had been predicted by the unfortunate tribal leaders in the interior. French gun-runners in Djibouti ran dhow-loads of 1874-pattern Le Gras rifles and ammunition into Las Khorai and harbours to the east, where the Mullah’s men were prepared to pay up to six camels for one rifle. The Royal Navy ship HMS Cossack and the Italian warship Governolo carried out joint patrols, stopping and searching dhows, but many more cargoes got through than were seized.

On 16th December 1901 a group of the Mullah’s mounted men suddenly surprised a large encampment of tribesmen at Idoweina. The Mullah assembled the tribesmen and announced that he intended to punish all tribes who had assisted the Protectorate Government, and that he would drive all the British out of the territory and that he would become the Somalis’ leader. The British Acting Consul-General, Captain H.E.S. Cordeaux, informed the Foreign Office that he was raising the levy to its former strength and he appealed for more British officers. Eric Swayne was ordered back to Somaliland to resume military command.

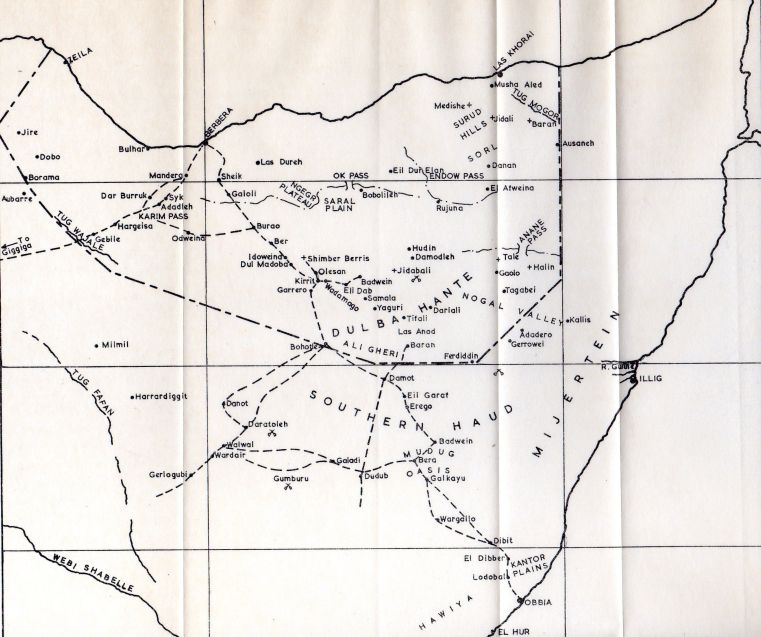

|

| Above: Somaliland Map |

British plans and reinforcements

The Foreign Office sent a cable to British Central Africa (now named Malawi) instructing that two Sikh Maxim gun sections and 300 officers and African Askari be prepared for operations in Somaliland. However the Foreign Office adopted a defensive pose to Cordeaux, stating: ‘that His Majesty’s Government do not wish to be drawn into a pursuit of the Mullah, and that operations should, so far as possible, be of a defensive nature’. Despite this Cordeaux and Swayne got on with doing what they could see needed doing and the discharged levies were re-called to service. Swayne now had a force of 1,500 men, 200 of them mounted on camels, and he obtained approval to recruit 500 additional infantry levies.

The Aden garrison supplied an officer and 100 Sepoys to man the coastal stations, and this allowed all the Somali soldiers to be moved into the interior. Swayne also requested artillery from Aden, and a battery of six 7-pounder guns was located in the stores. These guns were unfired and had probably been left behind after the British invasion of Abyssinia in 1868. The battery, complete with camel saddles, was sent to Berbera under the command of Captain J.N. Angus, Royal Artillery. Angus trained Somalis from 6 KAR to be gunners; four guns were placed in posts as part of the defences and two guns were used with camel transport as a mobile battery.

The Mullah’s dervishes continued their depredations against tribes considered to be hostile, acting roughly by spearing women and children when they wished to impose authority. The British believed that the Mullah now had over 12,000 followers, at least 600 of then being riflemen and many of them being mounted.

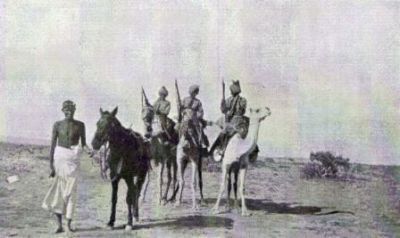

Right: Somali Camelry

Right: Somali Camelry

First moves

On 26th May Swayne marched south from Burao with a Field Force of 1,200 Somali infantry, 50 mounted infantry on ponies, 20 mounted infantry on camels, three maxim guns and the two 7-pounder guns of the mobile battery. About 1,000 camels were marched along either to carry supplies or to be used as rations. A garrison of 150 men remained at Burao and 100 other men manned a masonry blockhouse that had been constructed at Las Dureh. The contingent of Askari from British Central Africa had not yet arrived. The Mullah was reported to be at Baran, waiting to raid the British line of communication when his scouts advised him of an opportunity. At this time an outbreak of the bacterial disease glanders destroyed half of the British ponies, severely reducing the mobility of the mounted infantrymen.

Swayne halted at Bohotle and built a stockaded fort there to command the wells and house the reserve stores. The Mullah withdrew his main body to Erigo, one day’s march north of the large Mudug oasis in Italian Somaliland. This meant that Swayne would have to cross the waterless Haud desert to bring the fight to his enemy, and British troops would be dissipated in guarding Bohotle and the route back to Berbera. In anticipation of an enemy move into Italian territory the British force was accompanied by the Italian liaison officer Captain Count Lovatelli.

The Somali officer Ressaldar Musa Farah (mentioned in despatches for his influence in Somaliland and his gallantry in battle during the First Campaign) with 50 levies collected an irregular force of 5,000 friendly tribesmen. He then moved swiftly across a 160 kilometre-wide section of the Haud to attack the Mullah’s western encampments. Musa Farah utilised the speed and stamina of his Somalis to surprise the enemy, killing ten of them and capturing 1,630 camels, 200 cows and 2,000 sheep.

Due to a shortage of camels carrying water cans Swayne’s main body could not cross the Haud so he moved east. A column of mounted troops and spearmen under the Chief Staff Officer, Captain and Local Lieutenant Colonel A.S. Cobbe DSO, (32nd Sikh Pioneers, Indian Army and 1 KAR), was detached to raid the enemy encampments near Gerowai further to the east. Cobbe killed 140 of the dervishes and captured 3,900 camels and 12,000 sheep for a loss of seven men killed and one man severely wounded. A detachment of 200 dervishes had been located in a stone fort at Halin, and Cobbe attacked and destroyed this, seizing Le Gras rifles and more animals. The livestock captured by Musa Farah, Cobbe and other officers were useful additions to the British transport and catering departments, but they tied Swayne down with a cumbersome logistical tail that needed to remain near water holes and wells. By the end of July the Field Force was herding 12,000 camels, 35,000 sheep and 500 cattle and also protecting about 8,000 displaced tribes people.

Left: Making loads for burden camels

Left: Making loads for burden camels

The battle at Erego

During August and September the Field Force continued skirmishing with hostile encampments, and back-loaded captured stock towards the coast. Major P.B. Osborn DSO (Oxfordshire Light Infantry and 3 KAR), commanded a 6 KAR Mounted Infantry Company and was responsible for escorting stock and sick soldiers and tribes people back down the line of communication. The dervishes watched and opportunely raided British supply convoys.

The strength of the 2 KAR Askari force from Central Africa had been increased to half a battalion, and the first contingent landed at Berbera on 22nd August. It immediately marched inland, being tasked with arriving at Bohotle on 22nd September. Also a further 60 Sikhs had been requested from Central Africa to be used to boost the coastal garrisons. In early October the Inspector General of the King’s African Rifles, Brigadier-General W.H. Manning, arrived in Somaliland. His task was to supervise the line of communication and not to interfere with Swayne’s tactical command.

On 2nd October Swayne, now at Baran, decided to move and the 250 Askari of 2 KAR caught up with him that evening, having left a Sikh contingent at Bohotle to bolster the levy garrison. Rain had fallen on the Haud and pools of water were available on the intended Field Force route. Three quarters of the British ponies and riding camels were incapacitated by undernourishment due to lack of rain and good grazing, so most of the 1,250 men that marched south on 3rd October were African and Somali infantry. Four thousand camels accompanied the troops, half carrying baggage and the other half providing meat on the hoof.

Although Swayne did not mention the fact in his after-action despatch, it is likely that the Mullah practised a successful deception plan to make the Field Force march into an ambush. Captain Angus Hamilton, who was serving with 6 KAR, mentions in his book Somaliland that three dervishes had come into a British position claiming that the Mullah’s troops were at Erego and were prepared to surrender.

The Field Force moved down the large Erego valley. The ground in the valley was a mixture of desert and thick bush about three metres high which carried small hooked thorns on the branches. Swayne marched his men over 100 kilometres down the valley until on 6th October scouts reported that the dervishes were positioned about three kilometres ahead. A large square was formed with the two 7-pounder guns in the centre of the front face. Recently-enlisted levies were placed on either side of the guns but these levies apparently had no officers with them. Companies of 6 KAR Somalis extended the front face on both sides and 2 KAR Askaris protected the flanks. The transport animals followed behind the square and two companies of levies and one company of Askaris brought up the rear. The bush was extremely dense, impeding both movement and visibility. Each man could only see five or six of his comrades. A Maxim gun was positioned to the left of the front face of the square and three others were deployed to the right flank.

It appears that Swayne was led to believe by a dervish prisoner that a large clearing lay just ahead, and so he advanced the square. Soon enemy riflemen firing from previously-prepared pits engaged the 2 KAR Askari on the right flank at 20 metres range. The Askari stood their ground against the dervishes who now attacked with hordes of spearmen carrying small shields, a couple of throwing spears and a lance. The spearmen shouted “Allah! Allah!” as they charged. The British Maxim guns broke up this attack after about five minutes of fighting. A second dervish attack was mounted on the same flank and was repulsed, but the thousands of British camels had panicked and would not halt when commanded to. As the camels trotted out of the left side of the square Dervishes got in amongst them and directed them into the surrounding bush where the loads were scattered.

A fierce and successful attack was now put in on the left face of the square. The 6 KAR gunners continued to serve their guns despite taking heavy casualties, firing case shot (shells filled with metal balls) into the densely-packed attackers whose clothing often caught alight due to their proximity to the gun muzzles. The levies on the left of the guns broke and withdrew rapidly for 350 metres causing a collapse of the left corner of the square. The Maxim gun, which had not yet fired, was dropped in dense bush and lost. The withdrawal now crumbled the entire front face of the square apart from the gunners, who stood their ground.

Eric Swayne retrieved the situation himself be re-forming his Somalis and leading a costly charge forward. The square was re-established but Captain Angus was dead, shot through the head whilst he commanded his guns. The Field Force Second In Command, Major G.E. Phillips DSO, Royal Engineers, who had commanded the troops around the left corner of the square, was killed whilst aiming at a dervish who fired at him first. Captain W.D. Everett, Welsh Regiment, was severely wounded whilst commanding a company in the rear face of the square which was also heavily attacked. Major T.N.S.M. Howard, West Yorkshire Regiment, was slightly wounded.

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stanhope Cobbe had acted with great gallantry whilst the front of the square disintegrated, and he was later awarded a Victoria Cross with the citation:

6th October 1902 – At Erego, Somaliland, the retirement of some companies left him alone in front of the line with a Maxim gun. He brought it in single-handed and worked it gallantly. Then, seeing an orderly lying wounded 20 yards from the enemy, he dashed out and carried him to safety under heavy fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Cobbe was in fact assisted by a Somali Sergeant who acted as his Number 2 on the Maxim gun.

Serjeant Allan Gibb, an Army Ordnance Corps Armourer-Sergeant attached to 2 KAR later received a Distinguished Conduct Medal. Lieutenant Colonel Swayne’s citation read:

He had charge of a Maxim. He at all times carried out his duties efficiently, and attracted my notice by his coolness in repairing a Maxim under hot fire.

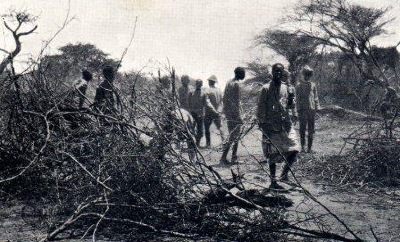

Left: Corner of a zareba under construction.

Left: Corner of a zareba under construction.

The fighting lasted for around two and a half hours before the dervishes withdrew and dispersed to loot the camel loads in the bush. Eric Swayne then re-organised his men and led a sortie through the bush driving the dervishes before him for three kilometres. Most of the camels and loads were recovered, but not the lost Maxim gun (it was finally recovered in 1920). The Mullah added a touch of courtesy to the proceedings by returning to Swayne two cases of whisky and a few boxes of spoiled tinned stores, with a note saying that if the British stopped fighting and allowed the dervishes to have a port on the coast, then hostilities would cease.

The Mullah had lost up to 1,000 men killed, wounded and captured. The British casualty list was 2 officers killed and 2 wounded, 56 soldiers and 43 transport spearmen killed, and 84 men wounded. But a square had been pierced and the British assumed that the dervishes would regard Erego as a victory. In fact time would show that the Mullah regarded the battle as a reverse, as many of his men were now understandably reluctant to charge against field and Maxim guns.

The conclusion of the campaign

After a night spent re-organising the Field Force Swayne marched out on 7th October to a temporary pool of rain water that scouts had located 10 kilometres away at Eyl Garaf. Swayne intended to continue operations against the Mullah whilst leaving his camels at the water pool. However on 8th September the company officers reported to Swayne that whilst the Yao Askari tribesmen in 2 KAR were philosophical about events, the Somalis of 6 KAR and the levies definitely were not.

Once the shock of battle was over the Somalis had collectively allowed a superstitious awe of the Mullah to constrain their thoughts. They now feared that the Mullah was invincible, and they were reluctant to face him in battle again so soon after Erego. Swayne stayed at Eyl Garaf for six days until the water dried up, patrolling against the dervishes. Then, unwilling to risk a serious confrontation with such an extended line of communication behind him, and with the morale of his Somalis still low, he withdrew in good order to Bohotle.

Although further reinforcements arrived from Aden and British Central Africa the campaign was now effectively over. The Mullah, smarting from the wounds to his force, withdrew into Italian territory to Mudug oasis and then on to Galadi. The dervishes did not return to British Somaliland until nine months later.

The Second Campaign ended as inconclusively as the First one had ended. Although Swayne’s Field Force had killed or wounded 1,000 dervishes and seized 25,000 camels, 1,500 cattle, 200 horses and 250,000 sheep, and had forced the Mullah outside British territory, dervishism still was a potent threat. The British could either go on the defensive or else plan to crush the Mullah before his reputation grew too strong amongst the Somalis. The latter course was chosen and a Third Campaign was planned, but with the understanding that the bulk of the British force would be comprised of regular African Askari and Indian Sepoys.

Awards

Eric Swayne’s military operational role in Somaliland was now almost ended and he was later appointed to be a Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (CB). In recognition of his raid across the Haud Ressaldar Musa Farah later received a gazetted promotion to Ressaldar Major and a special Sword of Honour from His Majesty King Edward VII.

In his despatch for the period 18th January to 1st November 1902 Swayne mentioned the names of 15 British and 2 Somali (Ressaldar Major Musa Farah and Jemadar Mahomed Yusuf) officers , one Sikh Sepoy and 5 Askari from 2 KAR, and 12 Somali soldiers and interpreters. Some of those mentioned went on to serve with distinction during the next two campaigns, whilst others were killed in action fighting against the Mullah and his dervishes.

A campaign bar to the African General Service medal was not issued until after the conclusion of the Fourth Campaign. The medal roll for the Second Campaign identifies 500 Somalis in 6 KAR plus 450 Somali mounted infantry and camelry men; 300 Yao tribesmen serving as Askari in 2 KAR; 60 Sikhs serving in 1 KAR; 12 British officers; and Sepoys from the Bombay Grenadiers who manned rear area garrisons and probably provided heliograph signals support.

|

| Above: Eric Swayne’s medals and decorations |

References:

Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India Volume VI, Expeditions Overseas, reprinted by The Naval & Military Press Ltd.

The Official History Of The Operations In Somaliland 1901-04, reprinted by The Naval & Military Press Ltd.

Hamilton, Angus, Somaliland, 1911, Hutchinson and Co., London.

Hayward, Birch and Bishop, British Battles and Medals, 2006, Spink, London.

Headlam, Major General Sir John, The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War, 1937, Royal Artillery Institution.

Jardine, Douglas, The Mad Mullah of Somaliland, 1923, Herbert Jenkins Ltd., London.

Magor, R. B., African General Service Medals, The Naval and Military Press, revision of 1993 edition.

McNeill, Malcolm and Dixon, A.C.H., In Pursuit of the “Mad” Mullah, reprinted in the Legacy Reprint Series.

Moyse-Bartlett, Lt. Col. H., The King’s African Rifles, reprinted by The Naval & Military Press Ltd.

Page, Malcolm, KAR – A history of the King’s African Rifles, 1998, Leo Cooper, London.

The London Gazette.

Source: Kaiserscross