On Sunday, 15th May, the United Nations (UN) in Somalia welcomed the conclusion of Somalia’s Presidential election, praising the ‘positive’ electoral process and peaceful transfer of power. Hassan Sheik Mohamud prevailed over Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Farmaajo’ to become Somalia’s new president. This election was anticipated to be a watershed moment for advancing long-awaited priorities in Somalia concerning peace and stability. James Swan, the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative for Somalia, stated, “I would like to congratulate the newly-elected President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud on his victory tonight,” while UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres conveyed hope that the new President moves swiftly to form an inclusive Cabinet and that the new government and federal states work closely together to advance critical National concerns. However, from the need for long-term political stability to urgent security challenges, the Mohamud administration has its work cut out.

In March alone, two suicide bombings killed 48 people in central Somalia, while an attack on an AU base earlier in May killed ten Burundian peacekeepers. Al Jazeera reports the attack was ‘the deadliest raid on AU forces in the country since 2015.’ President Mohamud takes office over a Nation that has endured conflict and clan battles with no strong central government since the fall of dictator Mohamed Siad Barre in 1991. The government has little control beyond the capital, and the AU contingent guards an Iraq-style “Green Zone.” As such, stakes are very high for the Somali people moving forward from last week’s election. This report will investigate the chances of meaningful peace and security progress in post-election Somalia.

Core Issues And Why They Persist

Somalia’s longstanding struggles with conflict and instability have myriad contributing factors both within and outside the country. From Colonial legacies, clan conflicts, terrorism, and adverse environmental conditions, the incoming Mohamud administration has much to account for. Since the collapse of the Somali State in 1991, no administration has been able to form a government that unites Somalia’s many constituencies and interest groups. Perhaps because of this, Annite Weber, the European Union (EU) special representative to the Horn of Africa, emphasizes Somalia’s need to build a political settlement first and foremost. She claims that “a settlement forms the basis for agreement on issues related to the federalization process and the rule of law. It would also lay the groundwork…for constitution-making and State building.” Weber’s point is supported by evidence from Human Rights Watch (HRW) in their 2022 World Report focusing on Somalia. HRW found that “all parties to the conflict in Somalia committed violations of International Law, some amounting to war crimes.” HRW indicts the Islamist group Al-Shabab, highlighting where they “conducted indiscriminate and targeted attacks on civilians and forcibly recruited children.” Equally condemned is “inter-clan and intra-security force violence,” which killed, injured, and displaced civilians, as did sporadic military operations against Al-Shabab by Somali government forces, troops from the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and other foreign forces, including the US Africa Command (AFRICOM).

As a result, progressive reform has stagnated. The government has failed to pass federal legislation on sexual offenses or key child’s rights legislation. As of 2022, Somalia is yet to establish a national human rights commission, something that has been pending since 2018. The link between a weak, divided State rife with conflict and the slow pace of political progress is clear. Moving forward from the May election, building a strong foundation by bringing together Somalia’s warring factions into a political settlement will be President Mohamud’s biggest challenge. However, we must also consider the impracticalities of applying Western-style ‘one size fits all’ policy prescriptions to the Somali reality. In his Master’s (MA) thesis at the University of New York-Buffalo, former president Farmaajo writes on this issue, saying of European Colonists, “Not only did they introduce one central, federal authority to the nomadic people in Somalia; they promoted a system of government based on the multi-party democratic system. This was totally foreign to the Somali pastoralist society.” Here Farmaajo makes clear both the need for a unifying political settlement and, crucially, the need for that settlement to be on Somalia’s terms.

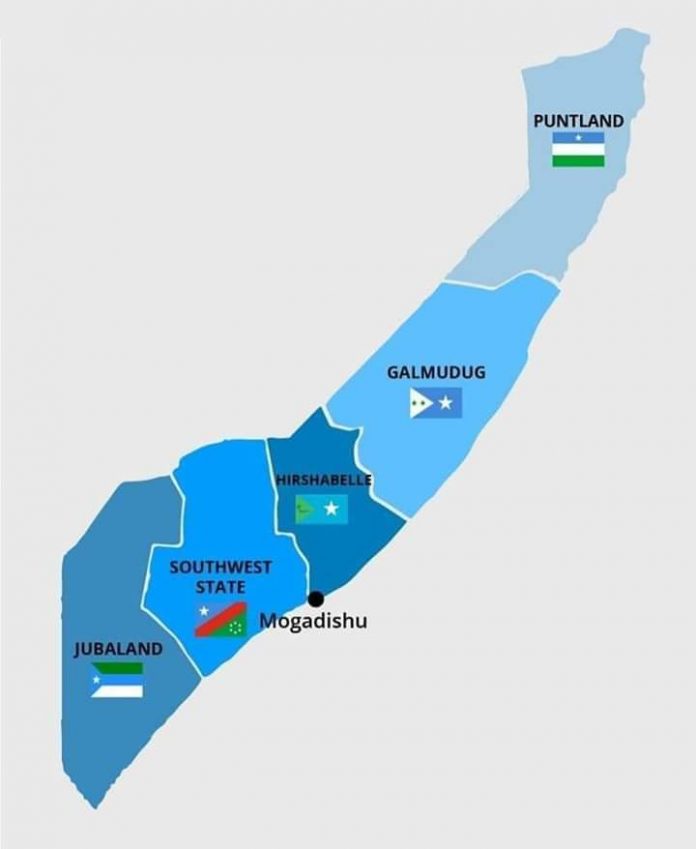

Where counterterrorism gets more media attention, these political issues lie at the root of Somalia’s struggle for peace and security. No injection of troops can bring stability. Military intervention often produces the opposite. Tunde Osazuwa, an activist and researcher with the Black Alliance for Peace, notes that the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies—a Pentagon research institution—found that “militant Islamist group activity in Africa has doubled since 2012” as AFRICOM’s presence on the continent deepened. In other words, Washington’s nominal counterterrorism has done much to empower terrorists. Foreign involvement will continue to produce these results until a consensus is found that empowers different Somali constituencies with confidence that their views will be represented and that leaders will be held accountable for their actions. This requires creating space for regional power centers to coexist under a federal system. Navigating these obstacles is key for building toward stability.

A Path Forward

May’s elections do nonetheless bring prospects for change. Firstly, massive conflicts across Somalia in 2021 were sparked by election delays, where parliament extended the presidential term on April 25 by two years. In response, armed confrontations broke out between security forces linked to different political factions in various districts of Mogadishu. The outcome was that between 60,000 and 100,000 people were displaced, according to the UN. Thus, the election, along with a peaceful transfer of power, sets the stage for President Mohamud to form a national unity government. It is important that conflicting political groups in Mogadishu are aware that violence is unacceptable and will not be rewarded. Moreover, the Mohamud administration must try to ensure that different voices are heard and represented in the new government, as there is a connection between violent uprisings and a sense of powerlessness and under-representation.

To achieve this, Somalia’s institutions must be seen as legitimate and just, from both a punitive and democratic standpoint. Here lies the core issue for many in Somalia. Despite a peaceful transfer of power, most of the 36 Presidential candidates were old faces whom many saw as having done little to stem war and corruption. This leaves Somalis with a sense that money changing hands is what determines political power instead of the popular vote. This mood is perhaps justified when gazing into Somalia’s electoral system. Clan elders pick delegates, who then select 275 members of the house of representatives and 54 members of the Senate. Once appointed, these lawmakers cast a vote to elect the next President, who in turn picks a prime minister. The PM then forms a government by appointing a cabinet. What is clear when analyzing this system is that even after May’s peaceful election, Somalia remains in the clutches of Clan elders and Political elites.

The masses, all the while, continue to be disaffected from a system that hasn’t had a one-person, one-vote election in decades. Given this evidence, reaching a political settlement representing the populace, resolving squabbles among an insular elite, and laying the foundation for a credible security apparatus is likely a long way to go. It is unrealistic to expect President Mohamud to rectify Somalia’s democratic deficit in the span of his term. Still, there are opportunities to build bridges, which can hopefully reduce violent clashes. A promising early sign is that Farmaajo called for unity in his concession speech. “Let us pray for the new president; it is a very tedious task,” he said. “We will be in solidarity with him.” This shows an appetite for reconciliation, while Somalia’s international partners appear committed to cooperation. This optimism and teamwork are needed on Somalia’s long road ahead.

Organization for World Peace