The city of Hargeisa, capital of the Republic of Somaliland, was almost completely destroyed by the Siad Barre regime in the late 1980s, as Somalia slipped into the state collapse that resulted in famine, clan violence, civil war, and the rise of the Al Shabaab terrorist group. But while the international community pursued a series of top-down, externally-supported efforts to stabilise Somalia with little success, in Somaliland a bottom-up, self-generated peace process restored security, and a democratic, legitimate and effective self-governing region, centred on Hargeisa, emerged as the Republic of Somaliland.

This Discussion Paper investigates the successes and challenges of Hargeisa in the areas of social and economic development, critical infrastructure and services, security and international relations, and suggests areas where other African cities could learn from Hargeisa’s experience.

When Afrah and her family left Hargeisa in 1988 she was just seven years old; like many towns- people who fled that year, she remembers a very different city.1 Hargeisa was once the seat of government of Britain’s colonial Somaliland Protectorate and (for five days in June 1960) capital of the independent State of Somaliland. By the late 1980s it had morphed into a northern provincial city under socialist dictator Siad Barre’s epically dysfunctional Somali Republic and was rapidly col- lapsing. At least 80 per cent of the town’s buildings had been reduced to rubble, and more than 50 000 members of the region’s majority Isaaq clan had been massacred by government death squads in what observers later dubbed the ‘Isaaq genocide’.2 Even today, unmarked graves of dozens killed in the 1980s are still being discovered near Hargeisa.3 By late 1988 most of the city’s population of 500 000 had been put to flight by bombs dropped from MiG jets of their own Somali Air Force.4

When Afrah and her family left Hargeisa in 1988 she was just seven years old; like many towns- people who fled that year, she remembers a very different city.1 Hargeisa was once the seat of government of Britain’s colonial Somaliland Protectorate and (for five days in June 1960) capital of the independent State of Somaliland. By the late 1980s it had morphed into a northern provincial city under socialist dictator Siad Barre’s epically dysfunctional Somali Republic and was rapidly col- lapsing. At least 80 per cent of the town’s buildings had been reduced to rubble, and more than 50 000 members of the region’s majority Isaaq clan had been massacred by government death squads in what observers later dubbed the ‘Isaaq genocide’.2 Even today, unmarked graves of dozens killed in the 1980s are still being discovered near Hargeisa.3 By late 1988 most of the city’s population of 500 000 had been put to flight by bombs dropped from MiG jets of their own Somali Air Force.4

Eyewitnesses told of warplanes launching from Hargeisa Airport on the city’s southern outskirts, turning back to bomb the town from which they’d just taken off, then landing at the same airport to re-arm and repeat.5 It was one of Barre’s last acts of large-scale violence and repression before his brutal regime collapsed and he too was swept away. A regime MiG shot down in the fighting by local guerrillas of the Somali National Movement (SNM) now serves as a war memorial, perched on a plinth in downtown Hargeisa’s appropriately- named Freedom Square.

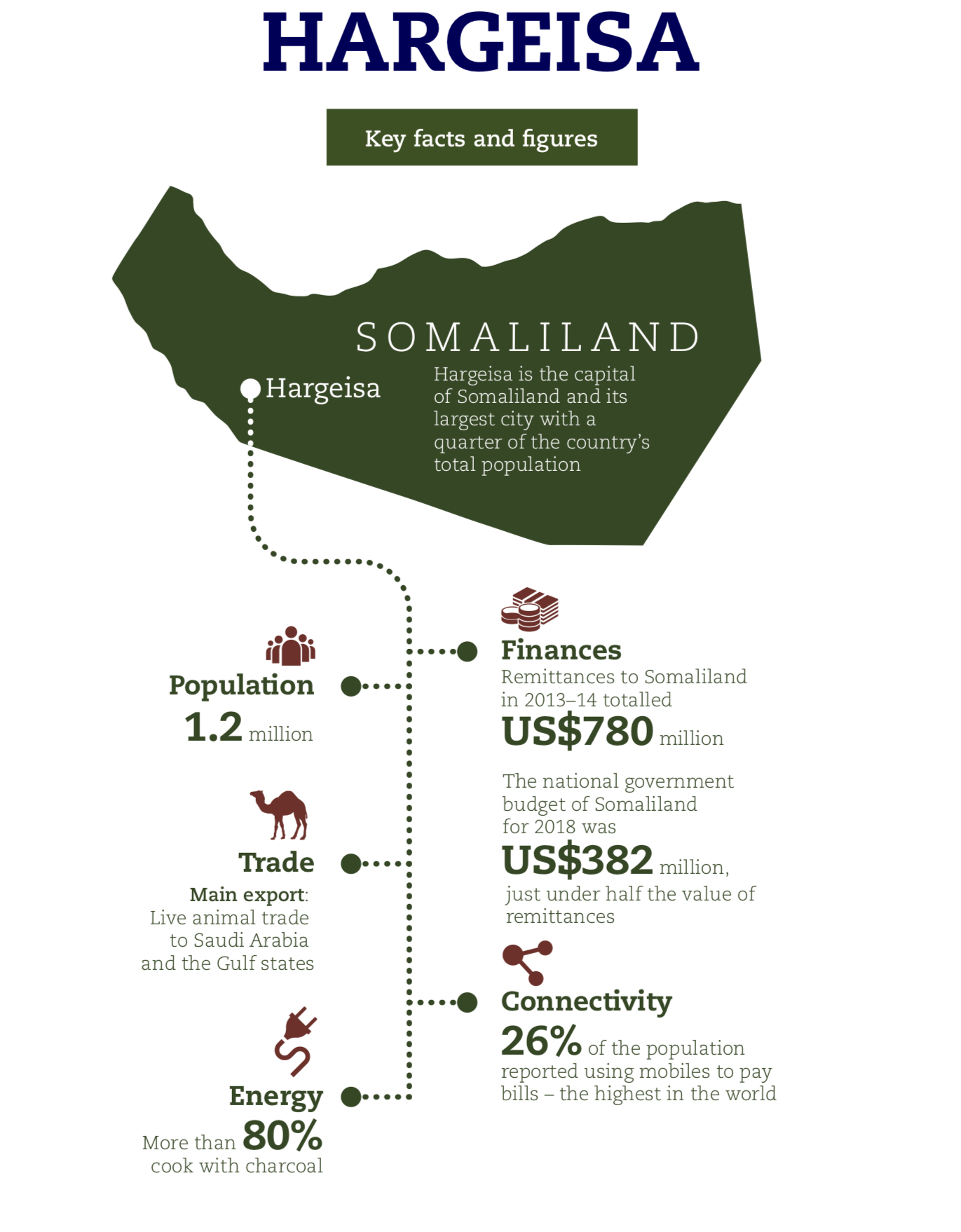

Looking out the aircraft window as you land today at Hargeisa Airport, with its modernised terminal and newly-extended runway, you see an almost completely rebuilt city. Driving into town you pass welcome signs from the Republic of Somaliland, official buildings bearing the govern- ment’s banner, neatly-uniformed unarmed traffic police directing a bustling flow of vehicles, and a series of thriving shops, hotels, cafes and restau- rants. Hargeisa’s population today is 1.2 million, roughly a quarter of the total population of Somaliland.6 The city has a safe, open, friendly vibe, even after dark – almost unbelievably so for

anyone who has spent time in Mogadishu, or even in other East African cities such as Mombasa, Maputo or Dar es Salaam.

Many buildings are under construction; market stalls stocked with fresh fruit and vegetables (mostly imported from Ethiopia) and manufac- tured goods (from Vietnam and China) line the roads. To be sure, those roads are absolutely ter- rible, sheep and goats graze the city streets, and a fine grey dust covers almost every surface. At 2:30 each afternoon – peak period for khat7, since trucks distributing the drug arrive from Ethiopia around 2pm, through checkpoints where officials col- lect excise – vehicles strop randomly in the street while satisfied customers wander with leafy- topped bunches of the tightly-wrapped twigs.8 But modern malls and supermarkets are also springing up; billboards advertise banks, boarding schools and universities, and the MiG monument – which, in photographs taken as recently as 2012 appears to sit in an empty square – is surrounded by stalls and overshadowed by bank buildings and telecoms offices.

Given all that, you could be forgiven for thinking you’d arrived in the thriving capital of a rapidly developing, well-governed, independent sovereign country, a town focused on commerce and construction, and determined – 30 years after its destruction by Barre – to put the past behind it. But you’d be wrong, for Hargeisa is an invisible city.

Invisible City

The sovereign Republic of Somaliland appears on no maps. It is listed in no official register of the world’s countries, has no seat at the United Nations and no international country code. Government officials are forced to use personal email addresses because there is no internationally-approved Somaliland internet domain, and the country is unrecognised by the international postal union, so the only way to mail something from Hargeisa is via the slow and expensive DHL shipping service.9 Instead, the country is described as the ‘self-declared but internationally unrecognised republic of Somaliland’ and considered by the international community to be a breakaway region of the Federal Republic of Somalia – the successor to Barre’s regime, inaugurated in 2012 after decades of lethal anarchy in the south, cobbled together by the international community with UN supervision and under the guns of an African Union peacekeeping force.

Everything in Hargeisa – from the peace treaty pulled together by visionary elders in 1991, to the city’s self-financed rebuilding, to the unrecognised state of which it forms a part, to the largely informal economy and homegrown political system that sustains it, is a bottom-up, do-it-yourself enterprise. This enterprise, evolving over the past 28 years through a remarkable process of civic self-help, emerged not only without much international assistance but, at times, against active opposition from the world’s self-appointed nation-builders and doers of good.

Even while the world was watching Somalia shred itself in a clan bloodbath and apocalyptic famine in 1991–93 (the setting for the book and movie Black Hawk Down, the defining image of Somalia for many westerners) an extraordinary process of grassroots peacebuilding was quietly taking place in the north. Over many months in 1991–93, Somalilanders met in the Burao, Berbera, Sheikh, and Boorame peace conferences, a series of local reconciliation meetings brokered by traditional elders, resulting in peace agreements which then proliferated throughout the former territory of British Somaliland, and its mostly Isaaq and Darod clan groups.10 A constitutional convention and subsequent regional reconciliation agreements formalised the establishment of an executive presidency accountable to a bicameral legislature, with a lower House of Representatives elected by the people, and an upper House of Elders elected by clans. A constitutional convention later confirmed this setup. Somaliland’s governance structure – which has been described as a ‘hybrid political order’ – may sound exotic, but the House of Elders has essentially the same function as the British House of Lords, or the Senate in Australia or the United States.11 It plays a key role maintaining balance among the clans and geographic regions that form an essential element of Somaliland

(and indeed greater Somali)12 life. This serves to contain the destabilising, often lethal, escalation of zero-sum competition among clan factions that has occurred elsewhere.

This practical experiment in state-building has proven remarkably robust: Somaliland today possesses an independent judiciary and a free press, and peaceful transfer of power between Presidents following free and fair elections has become the norm. It is also enduring, with 28 years of homegrown stability and internal peace offering a stark contrast to the internationally-enabled chaos and violence in south-central Somalia.

As the capital of a country that officially doesn’t exist, Hargeisa has no formal status. Yet, as a practical reality, it’s a thriving commercial hub, the seat of a government that considers itself sovereign, is regarded as legitimate by its population, and administers one of the more stable, peaceful and democratic states in Africa. Hargeisa has consulates from Turkey, Ethiopia and Denmark, and a special envoy from the United Kingdom, receives international flights from Dubai and Addis Ababa, and hosts UN agencies, international aid missions and Chinese, Kuwaiti and Emirati businesses. Invisible they may be, but Hargeisa – and Somaliland – are very real.

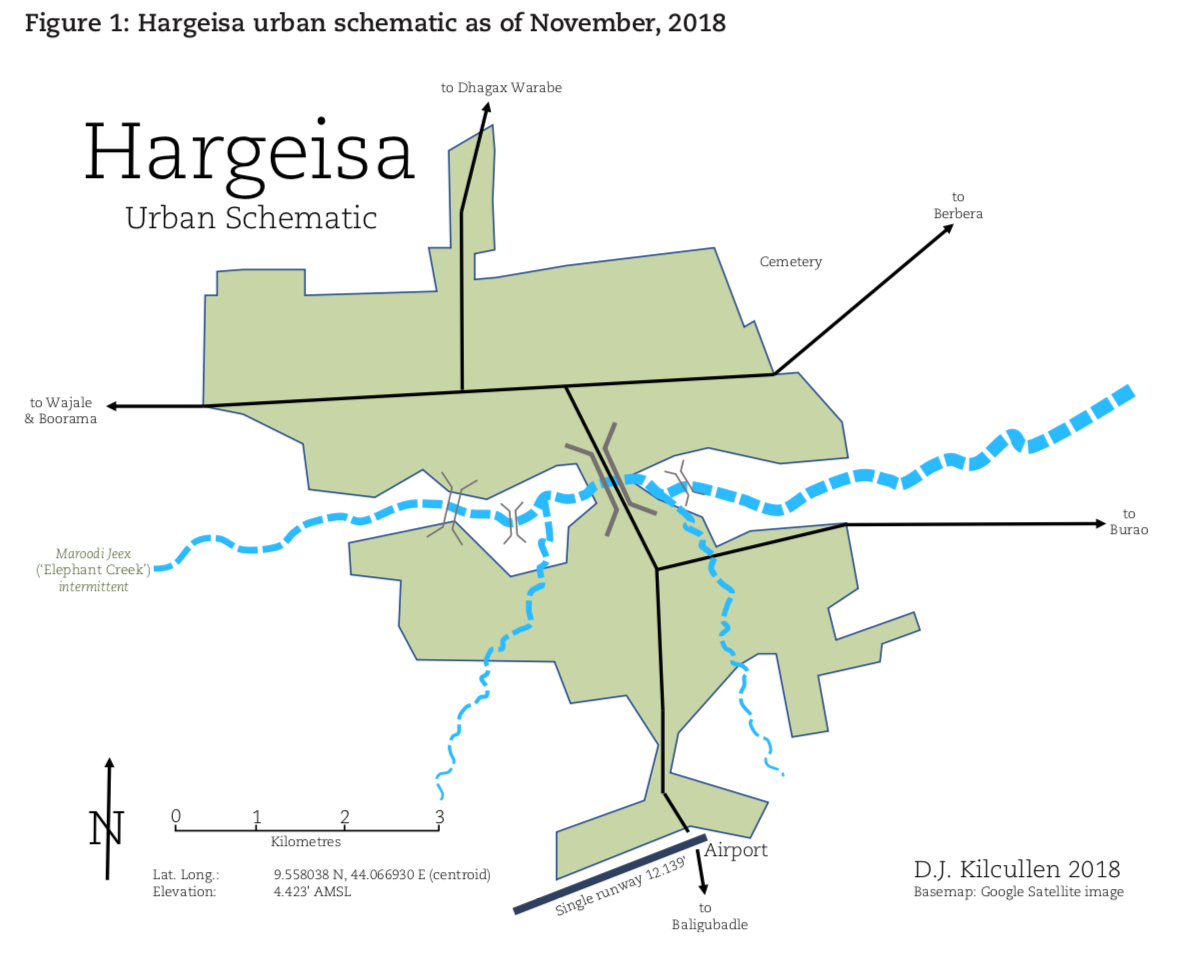

But there’s another, even more important, sense in which Hargeisa is an invisible city. If we think of it as simply a piece of urbanised terrain, ‘Hargeisa’ is a town of roughly 1.2 million people in the north-western Horn of Africa, its streets laid out in a grid pattern over about 33 square kilometres, situated on a cool plateau 4400 feet above sea level, in a rough hourglass shape (see Figure 1) astride the usually dry Maroodi Jeex (‘Elephant Creek’) and connected by road to the port of Berbera, two hours’ drive away on the Gulf of Aden. But the real city is vastly more than that.

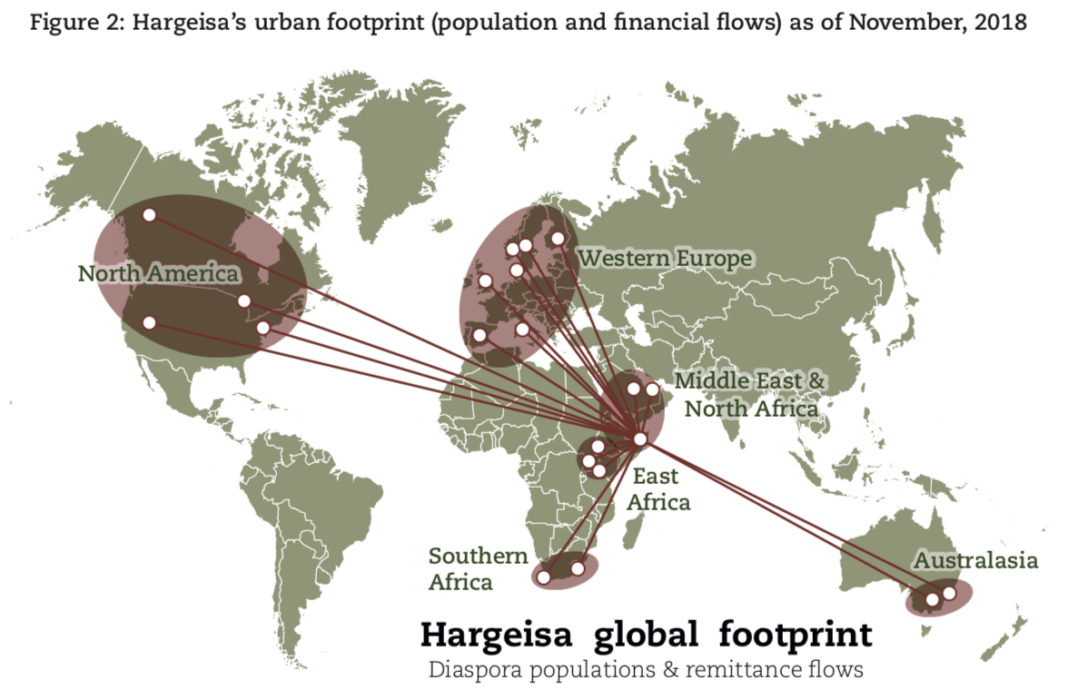

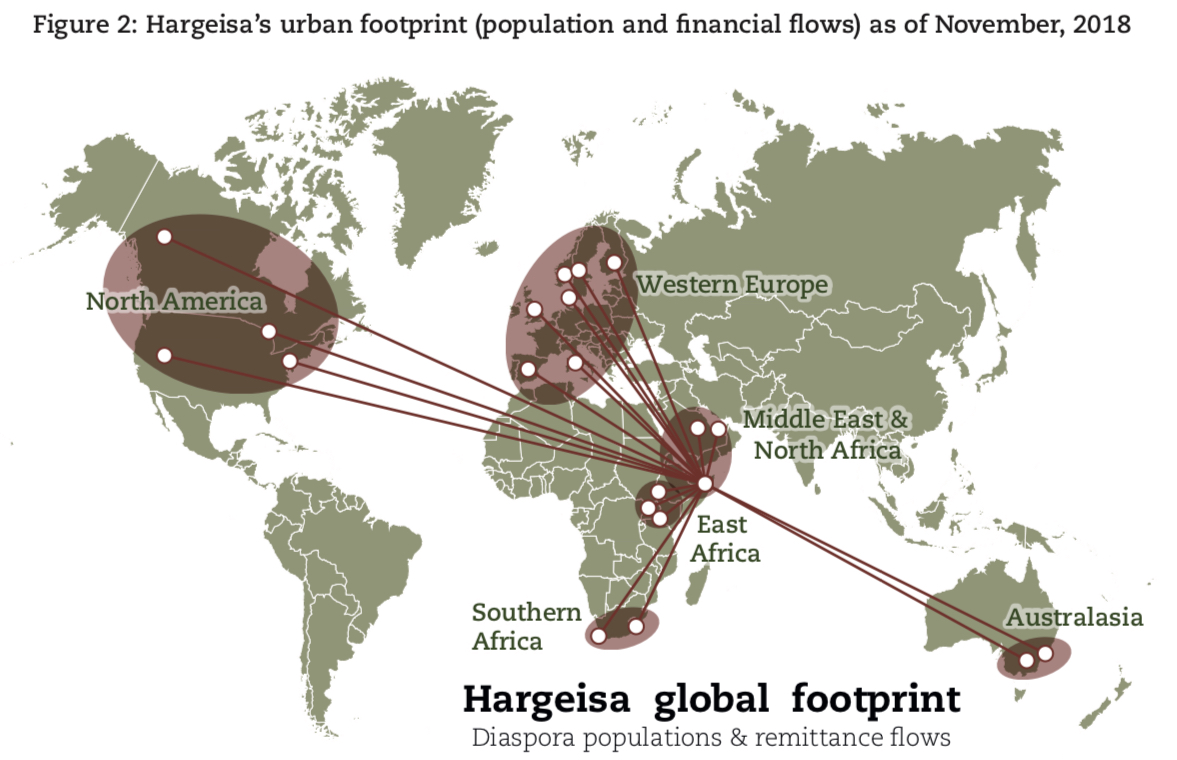

If, instead, we consider Hargeisa as a system, with the city’s relatively small area of urbanised terrain sitting at the centre of a vast social, political and economic ecosystem that includes not just the town itself but also its diaspora – the thousands of Hargeisans who live in Europe, America, Ethiopia, Kenya, Canada, Australia, the Gulf states and elsewhere, connected to their city through remittances, e-banking, mobile telephones, Skype, social media, family ties, business deals, visits and investments – then we have a much clearer idea of what the city is and how its political economy works.

Take Afrah, for example. Growing up in the United Arab Emirates and the United States, she is well-educated, with degrees in hospitality and tourism, an experienced manager and businesswoman who moved back to Hargeisa several years ago to look after her elderly mother and ended up launching a business with savings cobbled together during her time overseas. Today her tea room employs 25 people and does a lively trade serving civil servants from nearby ministries; she has reluctantly turned down offers to franchise her brand in other parts of the region. Like many business owners (and, seemingly, most of the officials who patronise her café) she holds two passports,

has relatives in several countries, speaks multiple languages, and travels regularly to Dubai for banking and to supervise shipments for her business or meet investors. Far from being a theoretical construct, the Hargeisan diaspora is an ever-present social, political and economic reality.

Somalilanders in the diaspora account for more than USD$700 million in annual remittances – and much of that money flows to or through Hargeisa.13 (For comparison, the total national government budget of Somaliland for 2018 was US$382 million, just over half the value of remittances.)14 In effect, the human and communication networks and financial flows centred on the city, invisible though they may be, are its lifeblood, even though many nodes in these networks are not physically in Hargeisa at all. On a map of this real but invisible Hargeisa (see Figure 2) significant parts of the city, much of its population – and most of its wealth – are in Amsterdam, Cape Town, Copenhagen, Dubai, Durban, Düsseldorf, Helsinki, London, Minneapolis, Nairobi, Oslo, Portland, Seattle, Sydney and Toronto. Understanding Hargeisa-in- Africa (Hargeysa ee-Afrika) in this way, as the tip of an iceberg, or one tree in a grove of trees with a single root system, is the key to seeing the real, invisible, Hargeisa-the-city (magaalada-Hargeysa).

Please Read the COMPLETE Discussion Paper HERE:

discussion-paper-04-2019-hargeisa-somaliland-invisible-city[108]

Good information about the place. Kudos to the elder for making it a safe and free place to visit. God boss Somaliland.