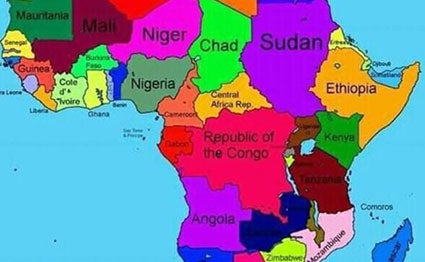

The Ethiopian government has been putting in a lot of overtime apologising for a map of Africa on the official website of its Ministry of Foreign Affairs that erased some countries.

The since-deleted map, published last weekend, got the goat of many Africans on social media for what, at first glance, looked like extreme effrontery.

It co-opted Somalia as part of Ethiopian territory, though retaining the semi-autonomous region of Somaliland.

It merged the two Congos, calling them the Republic of Congo. It erased South Sudan, going back to the Sudan as it was before the former’s independence in 2011.

The tiny kingdoms of eSwatini (former Swaziland) and Lesotho were eliminated; so was Equatorial Guinea.

RUTO’S VISIT

The map might have been the effort of a shaky-handed Ethiopian cartographer who had drunk too much Bedele Special the previous night, but one hopes it was more likely the work of an overzealous Pan-Africanist mapmaker.

For a true Pan-Africanist would argue that the sin of the map is that it didn’t kill off and merge more African countries.

The reality is that, even in 2019, there are still two opposed tendencies in the African state. Many states are smaller than they think they are and several others bigger than they imagine they are.

Perhaps the most significant story of the year on Kenya appeared in the Daily Nation early this month and is probably already forgotten.

It told of Deputy President William Ruto flying over Lotikipi Plains when his eyes caught some isolated huts.

He had his helicopter land nearby, and he went to visit the collection of huts in the remote Nayane Aroo area.

VISIBILITY

The villagers didn’t know who he was. Also, they neither spoke English nor Kiswahili, Kenya’s official languages.

Be that as it may, while there are Kenyans in what is not too far away from Ruto’s Eldoret backyard that don’t know who he is, there are worldly people in small towns in Europe and North America who know him.

In that sense, Kenya is both smaller and bigger than it is.

An African researcher doing work on conflict in the continent not too long ago landed in the Lake Chad Basin, that volatile region shared by Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria.

He narrates how he came upon some peasants selling food on the roadside, so he decided — through an interpreter — to seek their opinion on the political and economic woes of the basin.

Totally by accident, his questions wandered to the wads of currency notes they were clutching in their fists. They were Nigerian naira notes. The main peasant he spoke to knew it was money but didn’t know the currency.

He put it down to illiteracy, until he asked him in which country he was. The chap didn’t know. They were in Niger.

The Nigerian naira was the currency in that remote part of Niger.

He then asked if he could name any of the several countries neighbouring Niger (Nigeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Libya, Chad) and the fellow just gave him a blank stare.

His conclusion was that this was not just illiteracy. There simply was no consciousness among the peasants that their countries and the neighbouring ones existed as separate nations.

There were local chiefs, but their authority was not based on territory but cultural and spiritual constructions.

Likewise, we’ve written before about the vexing issue of demarcating the border between Sudan and South Sudan.

The good people at the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa working on it tell an incredible story.

BORDER LINE

Say, on a Monday, they have a meeting in an air-conditioned boardroom with Sudanese and South Sudanese officials.

They whip out and pore over the maps, lay rulers upon them and agree on the latitudes and longitudes of the borderline. Well and good.

On the Friday, the teams assemble at the physical border and bring out the map. “According to the latitudes and longitudes we agreed on on Monday, this is where the border line passes,” an AU official might say.

At that point, the whole thing goes haywire. “No, it is not,” a South Sudanese says, pointing to a point deep into (north) Sudan territory.

“For over 150 years, we always knew that the border is at that hill, and our grandfathers, and great grandfathers, grazed their cattle in the valley.”

“For us,” a Sudanese chimes in, pointing to a river five kilometres inside South Sudan, “since time immemorial, that was the border. Our people have fished in the river for generations and our culture is full of songs and poems about it.”

BACKLASH

Invariably, the meetings break down. The Sudan-South Sudan border remains unresolved.

Africans might not challenge the tyranny of their crooked politicians. But the tyranny of the map will be met with either fierce resistance or scornful disregard.

The fellow who drew that controversial Ethiopian map is as African as you can get.

By

CHARLES ONYANGO-OBBO

Mr Onyango-Obbo is the publisher of Africapedia.com and explainer Roguechiefs.com. @cobbo3