The UN’s main court for disputes between countries, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), ruled yesterday on a contentious case many years in the making: Kenya and Somalia’s dispute over the rights to a large slice of the Indian Ocean off their coasts.

While other news outlets analyze the politics and economics of the dispute, it’s PolGeoNow’s job to give you a clearer, more detailed explanation of its geography. And as shown in the three all-new map infographics below, that geography is a bit more complex than most news articles let on.

Scroll down to see each map at full size, along with concise explanations expanding on the information within the graphics…

Map 1: The Kenya-Somalia Maritime Dispute – Before the Court’s Judgment

|

| Map by Evan Centanni. Click to enlarge. Contact us for permission to use this map. |

This map shows the dispute between Somalia and Kenya as it was presented to the court. Kenya claimed that the boundary between the two countries’ maritime zones runs straight east along a line of latitude (similarly to boundaries with other countries farther down the coast), while Somalia claimed the right to a boundary running roughly perpendicular away from the coast, along a course equally distant from each country’s nearest land.

The dispute included not only the two countries’ territorial waters, but their much bigger exclusive economic zones (EEZ), which allow them to control oil and fish extraction, and their extended continental shelf claims, which grant economic rights beyond the EEZ, but only to seafloor resources such as oil. Because the EEZ and continental shelf aren’t technically part of a country’s territory under international law, only the small triangle of contested territorial sea near the coast is technically a “disputed territory”. For the same reason, the lines dividing one country’s EEZ and continental shelf from another’s aren’t technically “borders”, so experts prefer the more generic term “boundary”.

Between the disputed EEZ and disputed continental shelf areas, there was a zone known as the “Grey Area”, which is too far from Kenya to be claimed as part of the Kenyan EEZ, but still close enough to Somalia that it could be part of the Somali EEZ. Kenya claimed that this area was off limits to Somalia only because it falls south of Kenya’s claimed boundary line, which would then give Kenya the right to claim its seabed as part of the Kenyan continental shelf.

Map 2: Somalia v. Kenya – What the Court Decided

|

| Map by Evan Centanni. Click to enlarge. Contact us for permission to use this map. |

In its final judgment yesterday, the ICJ drew a new boundary to separate Kenya and Somalia’s sea zones, largely taking Somalia’s side, but also including some concessions for Kenya. Importantly, the court agreed with Somalia’s argument that the dividing line should mainly be based on equal distance from the countries’ coasts – in line with the method recommended by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) – even if that wasn’t how neighboring countries had done it.

Still, the judges did have some ears for Kenya’s argument that this “equidistance” line would lop off too much of the country’s potential sea resources, allowing Somalia and Tanzania to squeeze Kenya out just because of the unlucky shape of its coastline. Though Kenya’s previously-agreed boundary with Tanzania was placed off limits for consideration as a factor, the court still ended up concluding, in a split decision, that Kenya deserved some northward adjustment to the line to make up for the general concave shape of its coast. That decision ended up awarding Kenya around a quarter of the total disputed area, while the rest was given to Somalia.

Within the much smaller territorial sea proper, within 12 nautical miles of the coastline, the dispute proved less controversial.There, the court ruled unanimously to drawn the border very close to where Somalia had drawn it, only adjusting it slightly northwards. The adjustment was made after the judges decided to remove some tiny coastal islands from the equal distance calculations to produce a more common-sense result. (Neither the islands nor the related adjustment to the border are large enough to be visible on our map.)

Meanwhile, in another small win for Kenya, the court also unanimously dismissed Somalia’s request for reparations, which argued that Kenya had illegally violated Somali maritime space by conducting oil exploration and law enforcement exercises within the disputed territory. Since it had been unclear who the zone belonged to until now, and Kenya apparently hadn’t done any permanent damage, the judges all agreed that there had been no violation of Somalia’s rights.

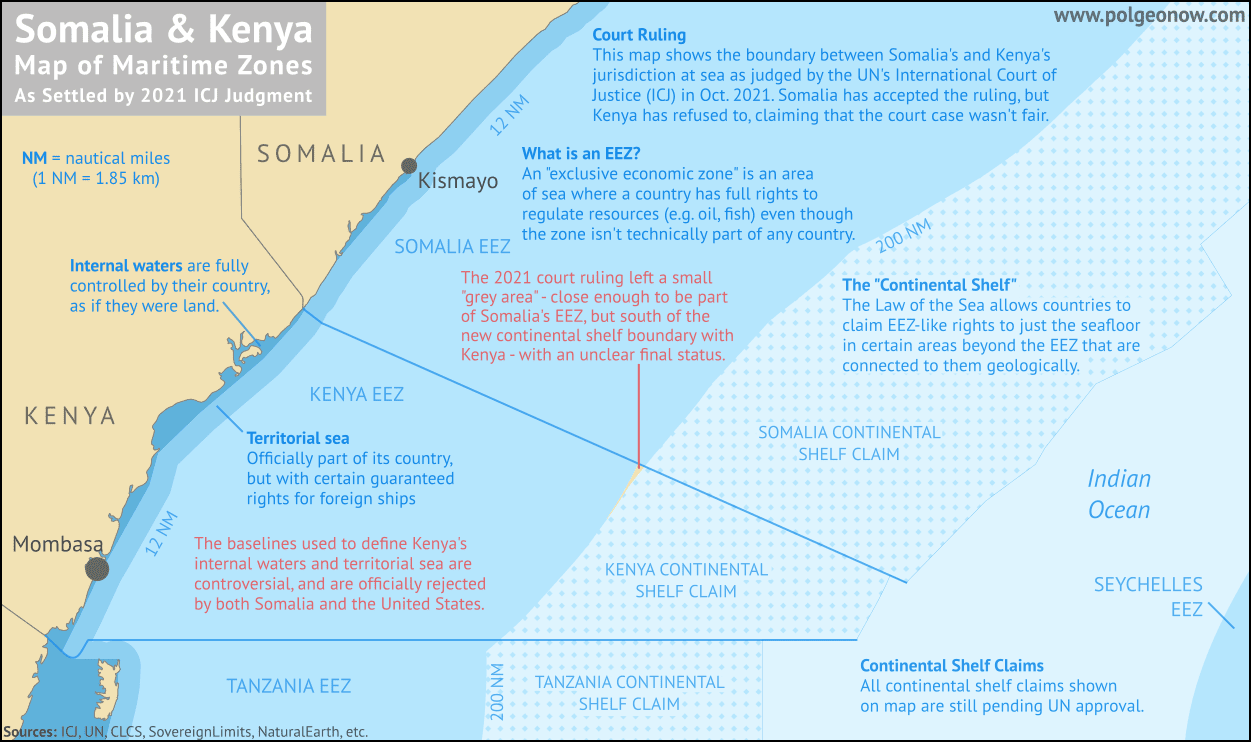

Map 3: Kenya and Somalia’s New Sea Boundaries as Settled by the Court

|

| Map by Evan Centanni. Click to enlarge. Contact us for permission to use this map. |

Our third map, then, shows the new configuration of Kenya and Somalia’s territorial seas, EEZs, and continental shelf claims according to the ICJ’s judgement. Notably, a small section of Somalia’s continental shelf claim falling southwest of the boundary has been invalidated, despite lying beyond the outer limits of Kenya’s claim. Meanwhile, Kenya’s EEZ and claimed continental shelf do narrow quite a bit the farther out to sea they get, but they don’t come to an almost completely enclosed point as they would have under Somalia’s claimed boundary.

This is, of course, all based on the premise that the court’s ruling is now the legal truth. According to its reading of international law, the court itself insists that its judgment is final and legally binding, and Somalia – which brought the case in the first place – has happily accepted the judgement. Kenya, on the other hand, has been arguing the whole time against the court’s authority – earlier focusing on arguments Somalia didn’t have the right to bring this case to court, and later on arguments that the court hasn’t treated Kenya fairly.

The end result is that Kenya’s government has flatly rejected the court’s ruling, and still considers its own original boundary claim to be valid, whether or not Somalia, the court, or the rest of the world agree. And since there’s actually not much the ICJ can do to enforce the ruling, Kenya might more less get away with ignoring the ruling for now.

With that in mind, a Map 4 is probably in order: one showing the new, reduced area disputed between Kenya and Somalia now that Somalia has given up the bottom slice of the zone but Kenya still claims the whole thing – a dispute that seems to exist in real practice whether or not it’s considered legally valid. Because the court judgement just came out yesterday, we’ve decided to let the dust settle a bit before making that map, just in case Kenya changes its mind or any new details come to light – but you can bet that we’ll be publishing one in the near future if everything continues as it is now.

Continental Shelf Claims and the “Grey Area”

So, why all this talk of “claimed” continental shelves? Well, the rules of international law, also approved as domestic law by most countries, say that any seabed claims past 200 nautical miles from land have to be reviewed and approved by an expert commission at the UN before they can take effect. That’s because there are specific, extremely technical rules governing which areas of seabed do and don’t count as part of the continental shelf (though “continental shelf” isn’t defined quite the same in international law as in geology textbooks).

Because neither Somalia’s nor Kenya’s continental shelf claims have yet been approved by that commission, the ICJ actually took care to clarify that the boundary it drew between those claims will only officially exist if and when they are approved. It was also defined as a line without a set endpoint, so it can automatically adjust to be as long or as short as necessary to accommodate any changes the commission makes to the shape of the claims.

In fact, the court was so cautious to avoid stepping on the continental shelf commission’s toes that it made a point of leaving the tiny remaining sliver of the “Grey Area” with an unclear status. Though the area lies south of the court’s prescribed boundary between the two countries’ seabeds, the ruling seems to leave open the possibility that the water itself could still be claimed for Somalia’s EEZ, especially given that Kenya’s claim to the continental shelf there could theoretically be thrown out by the commission.

Source: Polgeonow

Need ALL the details? You can find complete documentation of the court case on the ICJ website’s Somalia v. Kenya case files page, including the full text of each country’s submitted information and arguments, plus the court’s complete judgement of October 12, 2021, including dissenting arguments from judges who voted NO on the split decisions.