SINCE THE BRUTAL murder of Saudi dissident and Washington Post contributor Jamal Khashoggi last October, Congress has increasingly pressured the Trump administration to stop backing the Saudi Arabia-led coalition fighting in Yemen and halt U.S. arms sales to Riyadh. In response, President Donald Trump has repeatedly said that if the U.S. does not sell weapons to the Saudis, they will turn to U.S. adversaries to supply their arsenals.

“I don’t like the concept of stopping an investment of $110 billion into the United States,” Trump told reporters in October, referring to a collection of intent letters signed with the Saudis in the early months of his presidency. “You know what they are going to do? They’re going to take that money and spend it in Russia or China or someplace else.”

But a highly classified document produced by the French Directorate of Military Intelligence shows that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are overwhelmingly dependent on Western-produced weapon systems to wage their devastating war in Yemen. Many of the systems listed are only compatible with munitions, spare parts, and communications systems produced in NATO countries, meaning that the Saudis and UAE would have to replace large portions of their arsenals to continue with Russian or Chinese weapons.

“You can’t just swap out the missiles that are used in U.S. planes for suddenly using Chinese and Russian missiles,” said Rachel Stohl, managing director of the Conventional Defense Program at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C. “It takes decades to build your air force. It’s not something you do in one fell swoop.”

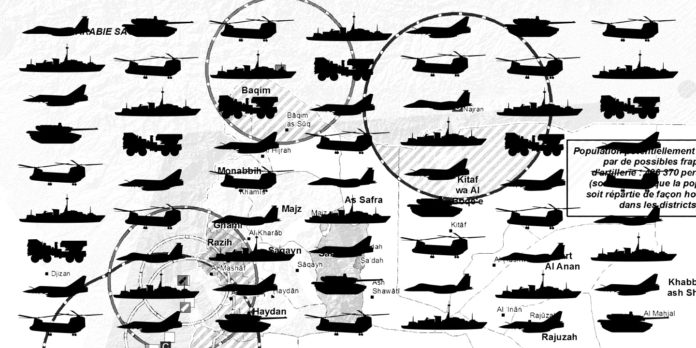

The Saudi-led bombing campaign in North Yemen primarily relies on three types of aircraft: American F-15s, British EF-2000 Typhoons, and European Tornado fighters. The Saudis fly American Apache and Black Hawk helicopters into Yemen from military bases in Saudi Arabia, as well as the French AS-532 Cougar. They have lined the Saudi-Yemen border with American Abrams and French AMX 30 tanks, reinforced by at least five types of Western-made artillery guns. And the coalition blockade, which is aimed at cutting off aid to the Houthi rebels but has also interfered with humanitarian aid shipments, relies on U.S., French, and German models of attack ships with, as well as two types of French naval helicopters.

The catalogue of weapon systems is just one revelation in the classified report, which was obtained by the French investigative news organization Disclose and is being published in full by The Intercept, Disclose, and four other French media organizations. The report also harshly criticizes Saudi military capabilities in Yemen, describing the Saudis as operating “ineffectively” and characterizing their efforts to secure their border with Yemen as “a failure.” And it suggests that U.S. assistance with Saudi targeting in Yemen may go beyond what has previously been acknowledged.

Since the beginning of the war, the U.S. has backed the coalition bombing campaign with weapons sales and, until recently, midair refueling support for aircraft. But the French report suggests that U.S. drones may also be helping with Saudi munitions targeting.

“If the RSAF benefits from American support, in the form of advice in the field of targeting, the practice of Close Air Support (CAS) is recent and appears poorly understood by these crews,” the document says. A footnote after the word “targeting” specifies that the possible U.S. “advice” refers to “targeting effectuated by American drones.”

Though the U.S. has denied engaging directly in hostilities against the Houthis, American MQ-9 Reaper drones – a reconnaissance drone with hunt-and-kill capabilities – have flown over Houthi occupied territory. After the Houthis shot down one of the drones in October 2017, it led to speculation that the U.S. could be using them to collect intelligence for the Saudis. Targeting being effectuated by American drones could mean that U.S. drones play a more active role in coalition targeting, like laser-sighting precision-guided munitions drops, for example.

U.S. Central Command strongly denied that U.S. drones have any operational role in coalition targeting. “The U.S. military does not provide that type of support to the Saudi-led coalition,” a CENTCOM spokesperson told The Intercept by email. “Our role with the Saudi-led coalition is advisory only. We provide intelligence and advise the coalition on best practices, air-to-ground space awareness, and the law of armed conflict.” French-made Leclerc tanks of the Saudi-led coalition are deployed on the outskirts of the Yemeni port city of Aden on Aug. 3, 2015, during a military operation against Shiite Houthi rebels and their allies. Photo: Saleh Al-Obeidi/AFP/Getty Images

French-made Leclerc tanks of the Saudi-led coalition are deployed on the outskirts of the Yemeni port city of Aden on Aug. 3, 2015, during a military operation against Shiite Houthi rebels and their allies. Photo: Saleh Al-Obeidi/AFP/Getty Images

DATED SEPTEMBER 25, 2018, the report was written to brief an October meeting of the French “restricted council,” a meeting of cabinet-level officials that included French President Emmanuel Macron, Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly, and Minister of European and Foreign Affairs Jean-Yves Le Drian. Its publication is likely to have significant political implications for the Macron government, which has steadfastly defended arms sales to Saudi Arabia, while simultaneously downplaying its own knowledge of how French weapons are used in Yemen.In January, Parly told a host on France Inter, a major French public radio station, that she had “no knowledge as to whether [French] weapons are being used directly in this conflict,” and that “we have recently sold no weapons that could be used in the course of the Yemen conflict.” She has also told journalists that French weapons “have not been used against civilians,” and described the country’s weapons exports as “relatively modest,” adding that “we don’t sell weapons like they’re baguettes.”

But the report shows that the Saudis and Emiratis have made much wider use French military hardware than the French government has admitted. Since the war began in 2015, the coalition has used French tanks and armored vehicles to reinforce the Saudi border and defend Emirati military outposts in Yemen. The Saudis have stationed French long-range artillery guns along its border, capable of firing deep into Yemen’s northern governorates, while the Emiratis have piloted French multiengine fighter planes, equipped with French laser-targeting technology. And both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have used French warships to enforce the coalition blockade against the country.

Though the report lists the French arms used by Saudi Arabia and the and UAE, it consistently notes that French intelligence has not observed the same weapons on “active fronts” with coalition ground forces, which are largely made up of Yemeni fighters loyal to former President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, as well as foreign mercenaries. One map notes the presence of French Leclerc tanks at a coalition base near the battle of Hodeidah, but the report also says that the UAE uses Leclerc tanks generally for defensive purposes.

In response to a detailed list of questions sent by Disclose, the French prime minister’s office sent a lengthy statement about France’s arms sales and its alliance with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The statement says that French arms sales are thoroughly reviewed and consistent with French and international law.

“France is a responsible and reliable partner,” the statement reads. “Offensive actions are regularly taken from Yemen against the territory of our regional partners – we have seen this with ballistic missile attacks or drones carrying explosives, for example. France maintains a constant dialogue with these partners to respond to their defense needs.”

It continues: “Moreover, to our knowledge, the French weapons available to the members of the coalition are mostly placed in a defensive position, outside Yemeni territory or on coalition holdings, but not on the front line, and we are not aware of civilian casualties resulting from their use in Yemeni theater.”

At no point does the report assess whether French arms have been used against civilians. One map, however, estimates that more than 430,000 Yemeni people live within range of French artillery guns on the Saudi-Yemen border.

The report is primarily concerned with the location of French weapons among coalition forces and says nothing about origin of Houthi weapons, some of which are known to have come from Iran. An appendix catalogues the major weapon systems used by the Saudis and Emiratis, but is not a complete list; it does not mention munitions, rifles, or several types of armored vehicles spotted by monitoring groups.

Overall, the appendix reinforces a point that observers of the war have made since the intervention began: that the military capability of the coalition has been created and sustained almost entirely by the global arms trade. In addition to the U.S., the U.K., and France, the report mentions radar and detection systems from Sweden; Austrian Camcopter drones; defensive naval rockets from South Korea, Italian warships, and even rocket launcher batteries from Brazil. Yemeni fighters aligned with the Saudi-led coalition-backed government man a frontline position at Kilo 16, an area which contains the main supply route linking Hodeidah city to the rebel-held capital Sanaa, on Sept. 21, 2018. Photo: Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images

Yemeni fighters aligned with the Saudi-led coalition-backed government man a frontline position at Kilo 16, an area which contains the main supply route linking Hodeidah city to the rebel-held capital Sanaa, on Sept. 21, 2018. Photo: Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images

THE REPORT DESCRIBES the Saudi-led air war in Yemen as “a campaign of massive and continuous airstrikes against territories held by the Houthi rebellion.” The coalition carried out a total of 24,000 airstrikes from the beginning of the war through September 2018, according to the report — a number that falls within the range estimated by the Yemen Data Project, an independent monitoring group.French intelligence has observed five types of piloted fighters flying over Yemen, all of which are NATO aircraft. The only non-NATO aircraft mentioned in the report is the Wing Loong, a Reaper drone knockoff produced by the Chinese. Export controls have prevented the U.S. from selling armed drones to the UAE, so Abu Dhabi turned to China to acquire them. Last year, the UAE used a Chinese drone to kill Saleh al-Samad, president of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, who was widely viewed as an advocate for engaging in the U.N.-led peace process.

Despite their vast technological superiority, the Saudis in particular are failing to meet their military objectives, the report says, identifying Saudi targeting as in need of improvement. And it describes the Saudis as less effective participants in air and sea missions, noting that the Emiratis are largely responsible for the blockade. It speaks more favorably of Emirati pilots, saying that they have a “proven” ability to use guided munitions, and that they perform up to NATO standards during bombing missions.

The report opens with a discussion of the battle to retake Hodeidah, a port city on the Red Sea and the entry point for most commercial goods and humanitarian aid into Yemen. The UAE predicted a decisive victory in Hodeidah, where fighting began last summer. But the intelligence report assessed that the “taking by force of [Hodeidah] appears still out of reach” for UAE-backed militias, despite their having nearly twice as many forces on the ground as their adversaries at the time it was written. However, the report notes them slowly moving to encircle and besiege the city by trying to retake critical junctions on the road between Hodeidah and Sana’a, the capital, which the Houthis control.

Before the offensive began, humanitarian groups identified a protracted siege as a worst-case scenario because it could largely stop the flow of aid to some of the regions of the country most in need.

“Commercial and humanitarian shipments coming through Hodeidah port are a lifeline, not just for people in Hodeidah city, but for much of Yemen,” said Scott Paul, a humanitarian policy lead at Oxfam America. “Setting up a long-term front-line and siege on the perimeter of the city would have a dramatic impact on national commodities markets and endanger anyone struggling to pay for basic necessities like food, fuel, and medicine.”

Despite calls from aid groups, the U.S. did not pressure the Emiratis to back off the attack. One U.S. official told the Wall Street Journal that U.S. policy was to display a “blinking yellow light of caution,” and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued a statement asking parties to respect the “free flow of humanitarian aid” but stopping short of calling on coalition forces to back off. Humedan Hussin Abdullah, left, sits with his father at a government hospital on Sept. 23, 2018 in Aden, Yemen. Abdullah is waiting to have shrapnel removed from his leg, an injury he sustained in an attack in Hodeidah province that killed two of his family members. Photo: Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images

Humedan Hussin Abdullah, left, sits with his father at a government hospital on Sept. 23, 2018 in Aden, Yemen. Abdullah is waiting to have shrapnel removed from his leg, an injury he sustained in an attack in Hodeidah province that killed two of his family members. Photo: Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images

Hodeidah saw some of the worst fighting of 2018, and the Norwegian Refugee Council estimated a total of 2,325 civilian casualties as a result. Aid groups also sounded the alarm about thousands of civilians who were trapped because of the fighting. An internationally brokered ceasefire in December slowed the pace of coalition airstrikes, but the ceasefire broke down in January and violence resumed.The French intelligence report also describes a massive operation by the Saudis to secure their border with Yemen, and says that five brigades of the Saudi army and two brigades of the Saudi National Guard — about 25,000 men — are deployed along the border. The troops are reinforced by 300 tanks and a battalion of 48 French-made Caesar self-propelled Howitzer guns capable of firing dozens of miles into Yemeni territory.

The “unspoken goal” of this border operation is to penetrate Houthi-controlled areas and eventually advance on Houthi strongholds in the Yemeni governorate of Saada, the report says. But it says the Saudis’ lack of mobility leaves them highly vulnerable to guerrilla attacks and that their strikes are too imprecise be effective against the nimbler Houthi forces.

“Despite the defensive means deployed, the rebels maintain their nuisance capability: artillery salvos, missile shots, improvised explosive devices, ambushes and infiltrations into Saudi territory,” the report says. “The addition of infantry combat vehicles in empty spaces between the tanks, in the summer of 2016, did not allow for an improvement in the efficiency of Saudi tactics.”